Registration is now open for Virtual Lecture: Making My Bed: Creating imaginative worlds with 3D embroidery. Hosted by Salley Mavor on April 16, on this virtual lecture she will talk about her 40+ year career creating imaginative worlds with 3-dimensional embroidery.

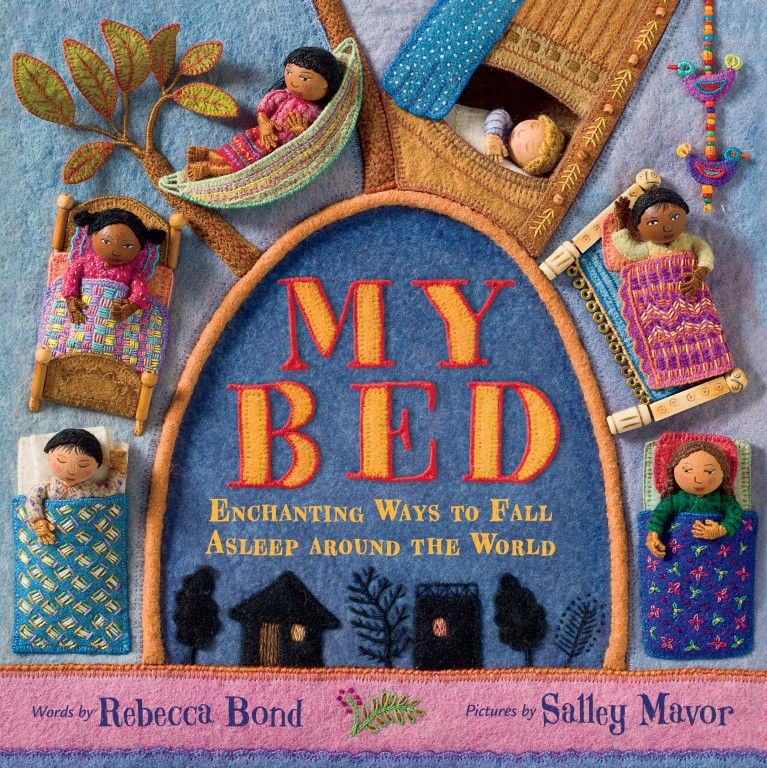

Your Virtual Lecture is called Making My Bed: Creating imaginative worlds with 3D embroidery, and it builds on your recent publication My Bed: Enchanting Ways to Fall Asleep around the World. Children’s books take on so many different kinds of subjects. What inspired you to focus on beds and bedrooms?

My first children’s picture book, The Way Home, came out in 1991 and I’ve illustrated many more since then. When Pocketful of Posies was published in 2010, I thought it would be my last. The 3-year process of making more than 50 illustrations was so all-consuming that I needed a break from the pressure of meeting deadlines. I also felt an urge to break away from the themes of childhood and explore what was happening in the adult world. I figured that if I was ever going to push myself artistically, now was the time.

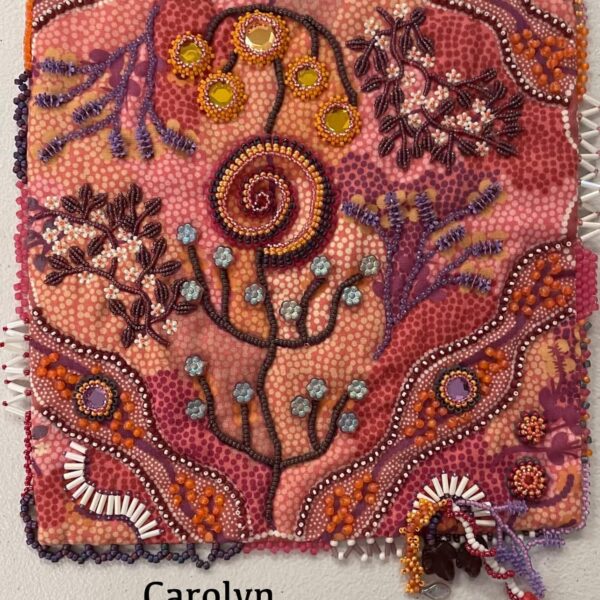

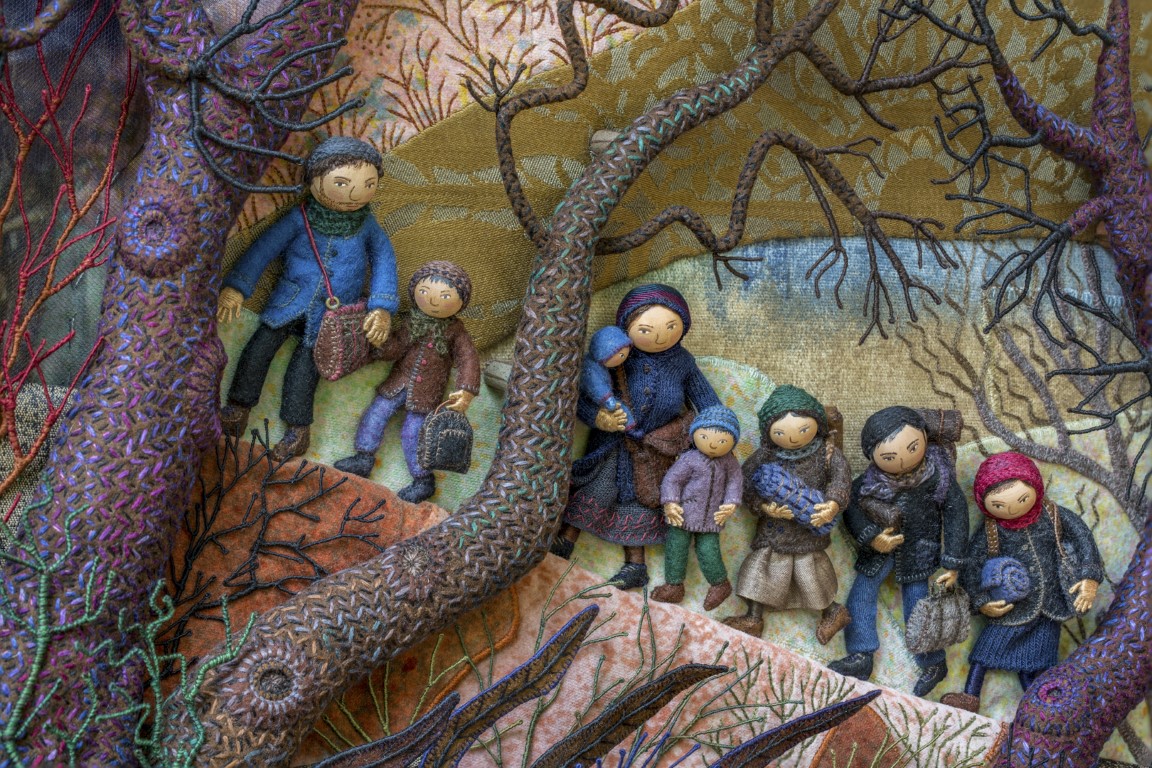

For several years I explored cultural diversity, migration, fashion, the natural world, and a range of social narratives, from the everyday to topical subjects. My new pieces were very satisfying to make; they were larger and took more time to complete than anything I’d done before. I felt more like an artist than an illustrator.

But, there was something about illustrating children’s books that I missed; the small, intimate format was so tempting! I also missed working within the wonderful community of children’s book publishing. And I wanted to create children’s faces again. An editor from Houghton Mifflin must have caught me during this nostalgic moment, because she talked me into illustrating My Bed.

It also helped that I could immediately picture scenes in my head when I read Rebecca Bond’s manuscript. I liked how her multicultural story celebrates our differences, while also bringing us together through the universal theme of children sleeping in their safe little beds. Creating the illustrations for this book was a wonderful adventure. I feel as if I’ve gotten to visit all the children in the places they live around the globe, even though I stayed home.

Did anything from your childhood bedroom make it into the book?

Many of the little details and found objects I use in my artwork are inspired by the home I grew up in, which was decorated in an eclectic style with furniture, textiles, and objects from all over the world. When my sister, brother, and I were young, our parents built and painted a folksy playhouse that influenced how I made some of the rooflines and cutaway interiors in my My Bed.

You studied Illustration at the Rhode Island School of Design. How did that training inform the artwork you create today? Why did you make the move from illustration to embroidery and working with fiber and fabric?

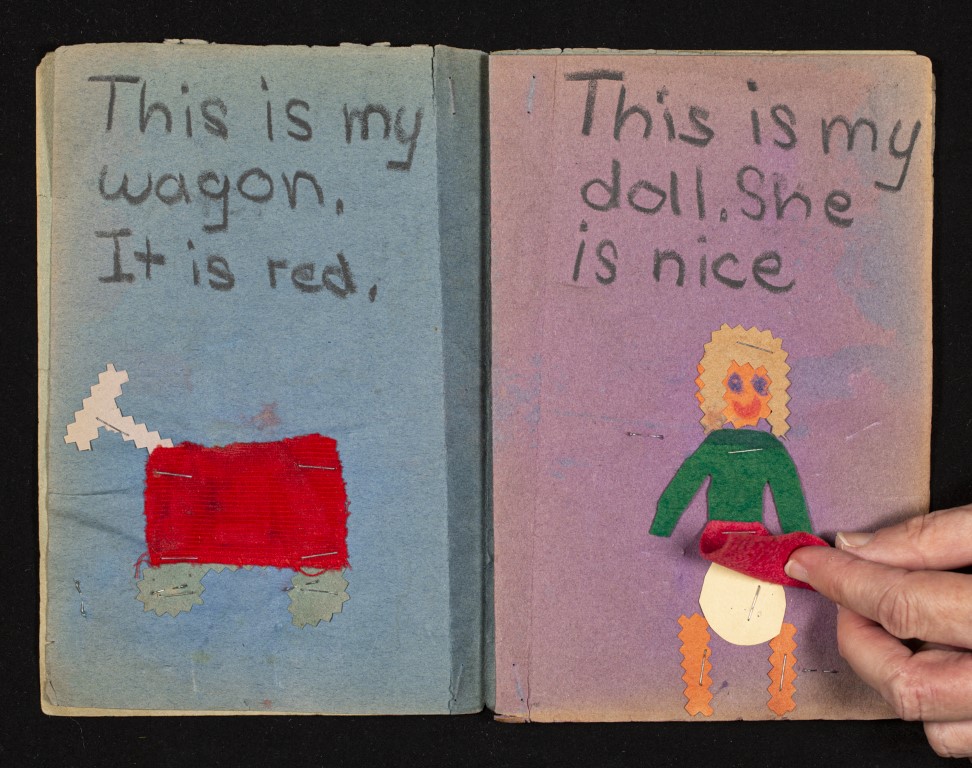

I discovered early on that it was easiest for me to express my ideas in sculptural form. Even as a young child, I remember feeling that crayons weren’t enough and that my pictures weren’t finished until something real was sewed, stapled, or glued to the construction paper. My sister and I spent hours sewing outfits and creating scenes for our Barbie and Troll dolls, a pastime that became an embarrassing secret once puberty set in.

During high school, in an effort to appear more grown up and serious about art, I concentrated on drawing and fine art. But, I continued to sew, stitch, collect interesting found objects, and privately dream about decorating my doll house.

At the Rhode Island School of Design during the 1970′s, there wasn’t an obvious place for someone like me, who was interested in many different materials and working methods and didn’t want to be limited to a particular discipline. I ended up choosing the illustration department because of its focus on communication and narrative imagery, rather than specific processes and art forms.

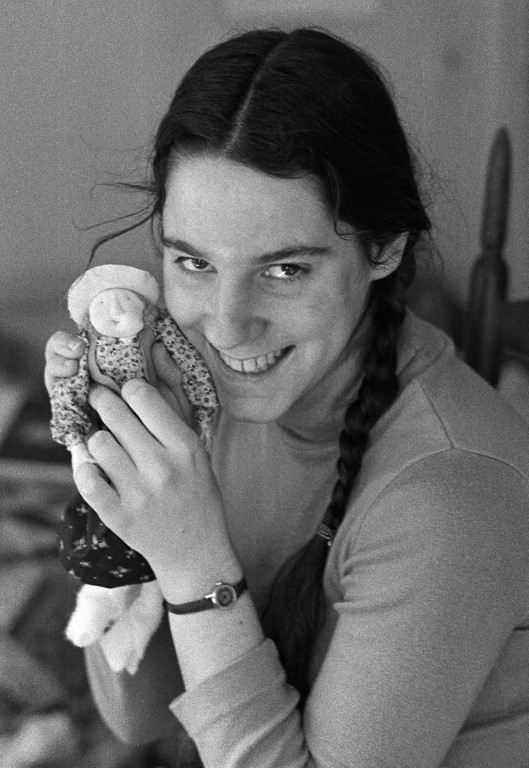

Fortunately, I was encouraged to forge my own path by a perceptive teacher, who noticed me sewing during a critique class one day. She said, “Do this for your illustrations!” With her permission to tap into my crafty and playful side, I stopped trying to translate the pictures in my mind’s eye through a brush or pen and found that I was happier and more energized while manipulating materials in my hands. I was no longer struggling to keep in step. With a needle and thread, I could dance.

For the rest of my time in art school, I explored different ways of working 3-dimensionally and taught myself how to make dolls and do embroidery.

As a self-taught fiber artist, where did you turn for inspiration and guidance?

I credit my art school education, where I learned the fundamentals of design and color, with giving me the tools and confidence to forge my own path. Having a background in basic art practices and visual thinking has been invaluable, especially when forming ideas and coming up with ways to communicate them.

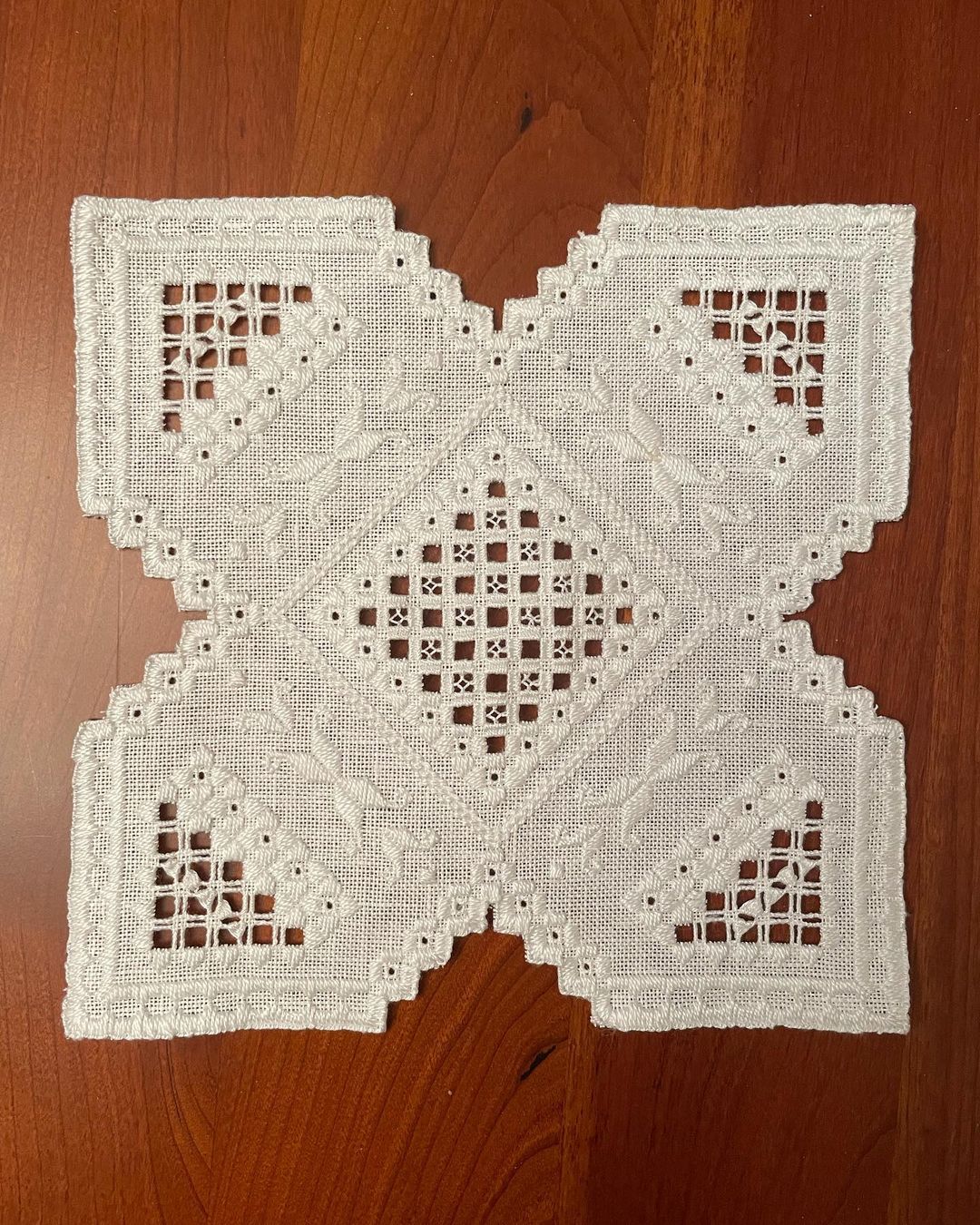

After seeing photos of stumpwork (the 17th century English raised embroidery technique) in the 1970’s, I was inspired to create my own versions of sewn and stitched 3-dimensional scenes in bas-relief. I work best independently and realized early on that my hands, imagination, and time were all I needed to grow artistically. I’m also resistant to taking instruction from teachers, especially if they are picky about doing things the “right way”.

I find inspiration everywhere, in nature, architecture, art history, fashion, and conversations with people. It can be anything that captures my imagination, no matter the medium. I’m never sure where my ideas come from, but they ferment for a long time as pictorial concepts in my head before showing up in my sketchbook and then as finished pieces.

Do you remember your first fiber project? What did you make?

I remember sewing little felt clothes for my Troll dolls when I was about 7. The different ways of sewing on snaps fascinated me; should the thread go outside of the snap holes or between the holes? I later learned to use my mother’s Singer Featherweight and by the age of 10 or 11, I was making animal shaped bean bags, which I sold at a local craft coop. This was in the mid-60’s, way before Beanie Babies.

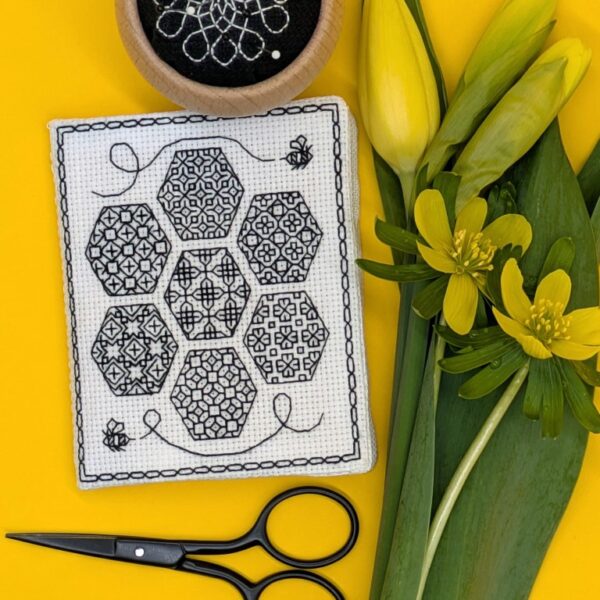

You’ve remarked on your website that you “only use half a dozen basic stitches” in your work? Can you share which stitches are your building blocks?

I learned basic embroidery stitches back in the 70’s from a simple instruction booklet and haven’t found the need to add more to my repertoire. I use blanket stitches, French knots, chain stitches, fly stitches, satin stitches, and some I don’t know the names of.

Recently, I posted a video of stitching moss with what I thought were French knots and was informed that I was actually making Colonial knots. I had to laugh because this distinction isn’t important to me. It’s just thread twisted around and knotted!

The tools and materials I use are very simple; I have no brand loyalty when it comes to thread or needles. I use close-up glasses, scissors, a thimble, an Ott-Lite, paint brushes, wire cutters, long nose pliers and a drill. All of these items make it possible to do my work. I don’t use a hoop and I’ve tried using a magnifier, but it just gets in the way. The thimble is my most precious tool, since it protects my finger tips from puncture wounds made by pushing the needle a thousand times a day.

You’ve acknowledged that the distinction between art and craft is “particularly fuzzy” in the world of needlework. Many needleworkers want to recreate your art pieces because the industry is built on patterns and inherited techniques, but artists don’t typically offer instructions so others can imitate what they do. What advice do you have for needlework artists who desire a similar singularity of expression? How did you pave your own path? What helped you find your way?

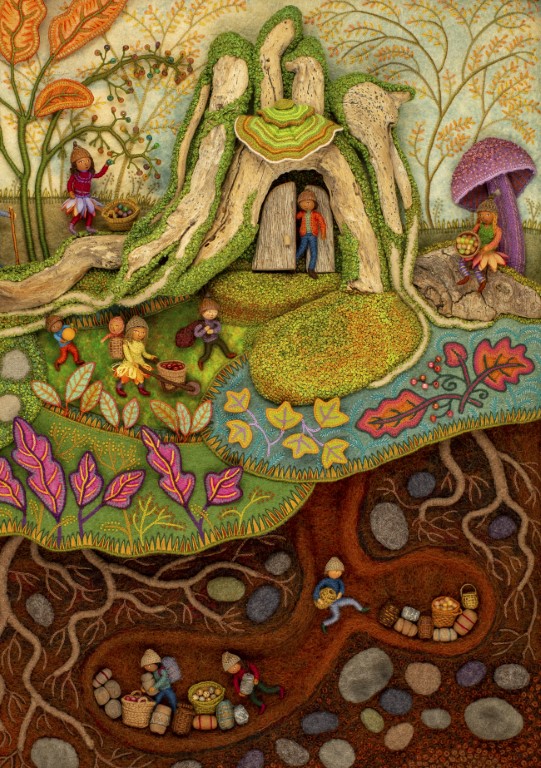

During all of my career, I have maintained that what I make is art, in the face of longstanding attitudes that needlework and embroidery are just women’s hobbies. To counteract this belief, I’ve concentrated on making art that is strong and compelling enough to transcend its medium. If people are first drawn in by the composition, message, and emotional resonance of my pieces, before noticing the materials and techniques, I feel that it is successful.

For those needlework artists who want to break away and develop a way of working that is more personal and expressive, I recommend a gradual confidence-building approach. Some people find the process of copying someone else’s designs relaxing, while others might find it constraining and limiting. If you’ve become accustomed to following a prescribed set of directions, it can be intimidating to take charge yourself.

I suggest doodling with a needle and thread, as a way of loosening up. Make your own color choices. Remember that there is no right way to embroider. Literally stitch outside of the lines. Think less about making perfect stitches and more about how colors and textures interact. And most importantly, play!

How do you begin to approach a new fabric relief piece?

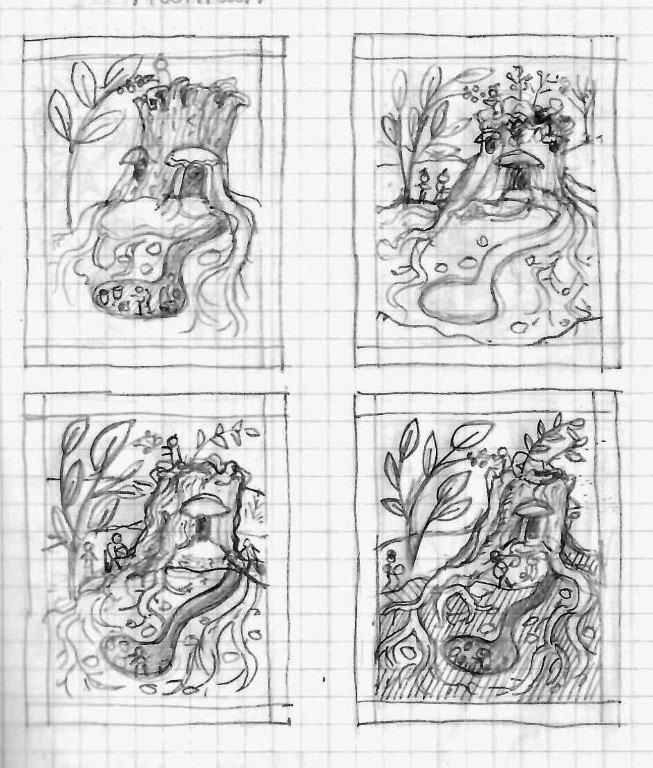

I both plan and improvise. First, I visualize a concept that I want to communicate. I draw many thumbnail sketches, working out the main design elements and composition of an idea. I then enlarge them to full size and print them out. These are simple drawings that take into account the overall visual and emotional dynamics of a piece. I figure out the details and color palette later when I start constructing and stitching the 3-dimensional parts.

You include this lovely quote on your website: “My aim is to breathe life and emotion into embroidery, an art form that is often perceived as purely decorative.” What function do you hope your embroidered artwork serves, beyond being beautiful?

I want to communicate with an audience in a visceral way, more through the heart than the head, which I think is the aim of most artists. I create these little worlds that people can immerse themselves in, that conjure up memories and feelings.

After seeing an exhibit of my work, one woman wrote, “It feels like your art is the antidote to, I don’t know, maybe most of the rest of the world.” I like to think that the combination of storytelling imagery, the use of familiar, yet intriguing materials, attention to detail, and fervent craftsmanship set my artwork apart.

Do you have a daily/weekly practice that you’d recommend to other embroiderers interested in honing their craft?

It takes great effort, devotion and persistence to maintain a creative practice and grow artistically. First of all, I think that one needs to believe that making art is important and not a frivolous waste of time.

Practicing techniques and putting in the time on a daily basis are also essential, so that the act of making becomes second nature, like mastering a new language or a new means of expression. But making good art requires more than technical skill, it takes developing a clear vision, which can take years.

I recommend allowing yourself to be mesmerized while you work — it will help you fall in love with the process. When you achieve that, your art will naturally become stronger over time.

What do you hope embroiderers take from the Making My Bed virtual lecture?

I want to inspire others to find their own way of expressing their uniqueness. It doesn’t matter what materials or processes they choose. Exploring different ways of working can help people discover what gives them satisfaction and what comes naturally. So much of making things and learning new skills involves struggle, but if one can reach a point where it feels like less of a struggle and becomes a personal expression, the experience can be life changing.