With September 15, 2023 marking the beginning of National Hispanic Heritage Month, EGA is excited and honored to have Dr. Lynne Anderson and Dr. Mayela Flores deliver a fascinating virtual lecture on Mexican dechados. Dechados, or samplers, played an integral role in the education of Mexican women and reflected the cultural and religious climate of Mexican life. We sat down with Dr. Anderson and Dr. Flores to learn more about their work.

Why are you interested in dechados and how did you come to work together?

Mayela: I’m an art historian who became fascinated with dechados in 2011 when I first encountered an example in the storage facilities of the Franz Mayer Museum in Mexico City. It was a dechado created by María de Jesús Martínez when she was five years old, around 1826-1836. This object was so intriguing to me that I immediately began researching Mexican samplers. Recently, I defended my Ph.D. thesis, which presents a comprehensive examination of the contexts in which dechados were made and a revision of the numerous assumptions that had shaped their identity. My objective was to present the complexities of Mexican women’s needlework culture during the 18th and 19th centuries when making dechados was widely practiced in Mexico and became an important phenomenon.

Lynne: I’m a professor of education who launched into the study of schoolgirl samplers in 2003 when I inherited three from my mother. I was fascinated by their connection to early female education and what we could learn from them about the educational experiences and opportunities of girls and young women in the 17th to 19th centuries. This led to establishing the Sampler Consortium, a membership organization of individuals interested in the study of historic samplers, and also creation of the Sampler Archive, an online searchable database of American schoolgirl samplers. I became interested in studying dechados after purchasing a colorful but undated silk-on-silk embroidery with no provenance. I was able to determine it was Mexican because of a motif depicting an eagle perched on a cactus, holding a snake – a variation of which is on the Mexican flag. This led to an investigation of other motifs and designs on Mexican needlework and research focused on understanding their origins.

We started working together after meeting in person in October of 2019 in Mexico City, and spending the better part of a day talking about Mexican female education and dechados. Since then, we have been collaborating to research and understand aspects of the history, particularities, and collecting practices related to Mexican dechados.

When did dechados first appear in Mexican culture?

Sewing and embroidery were an integral part of female education in New Spain (what is now Mexico) since the earliest colonists arrived from Europe in the 16th century – along with wives, daughters, and religious women who established Catholic institutions where needlework was taught. This meant that young elite girls undoubtedly practiced and recorded stitches and patterns on pieces of fabric – resulting in something we would recognize as a sampler, or, in Spanish, a “dechado.”

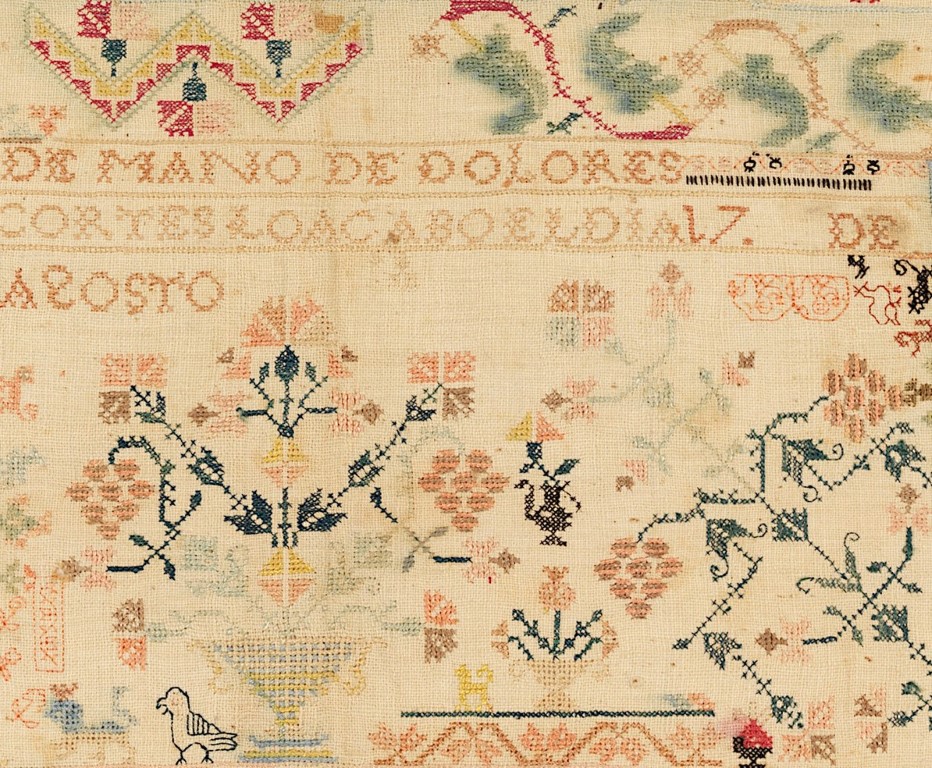

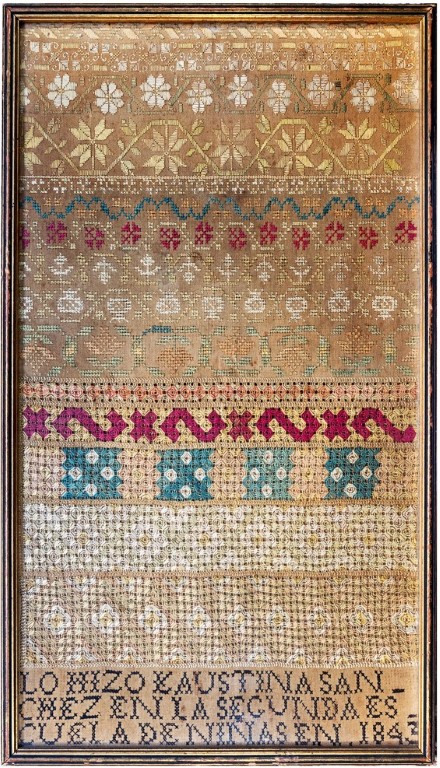

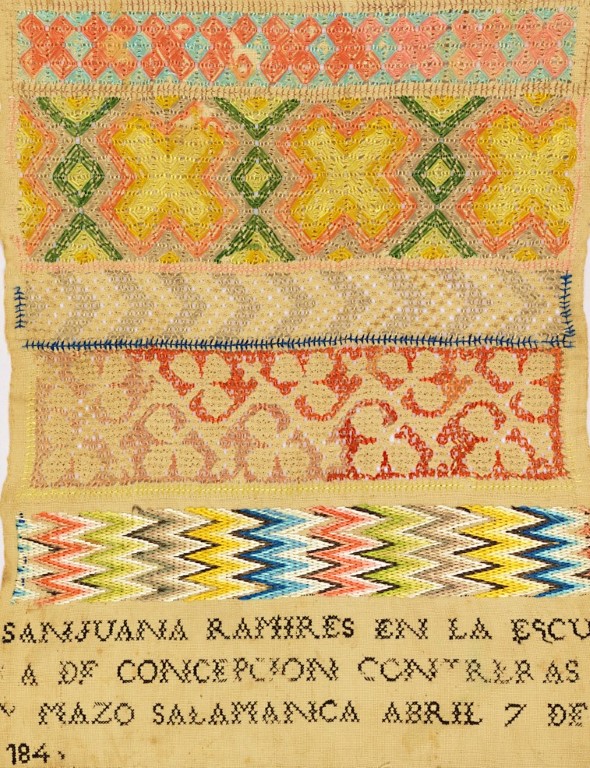

There are no known artifacts of this practice, however, until the 18th century. One of the earliest dated dechados was embroidered by Maryana de Andereyca (Mariana de Anderica), finished on December 11, 1783. It is in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (image below). (It is interesting to note that due to early 20th century interest in collecting Mexican textiles, including samplers, the majority of antique dechados made in what is now Mexico are found in museum collections in the United States.)

By the 19th century, embroidering one or more dechados had become a formalized part of the educational curriculum for girls and young women. Initially this was for girls of elite social and economic status, but by the middle of the 19th century, educational opportunities opened up for daughters of families with more modest means.

Why was the making of dechados an important feature in women’s education in Mexico?

Needlework was an important feature of women’s education in early Western European cultures, and by extension, the territories they colonized on the American continent. Plain sewing was essential for making clothes and domestic linens, and embroidery was the most common form of fancy sewing. In Mexico, creating a dechado that showcased a girl’s embroidery skills was an expected and essential accomplishment during her education. This gendered expectation was influenced by multiple factors, including the Catholic church’s idea of women’s role in society – the one responsible for domestic matters and caregiving.

Historically, samplers reflect the culture and time period in which they are made. What ideals and tenets did dechados reflect and uphold?

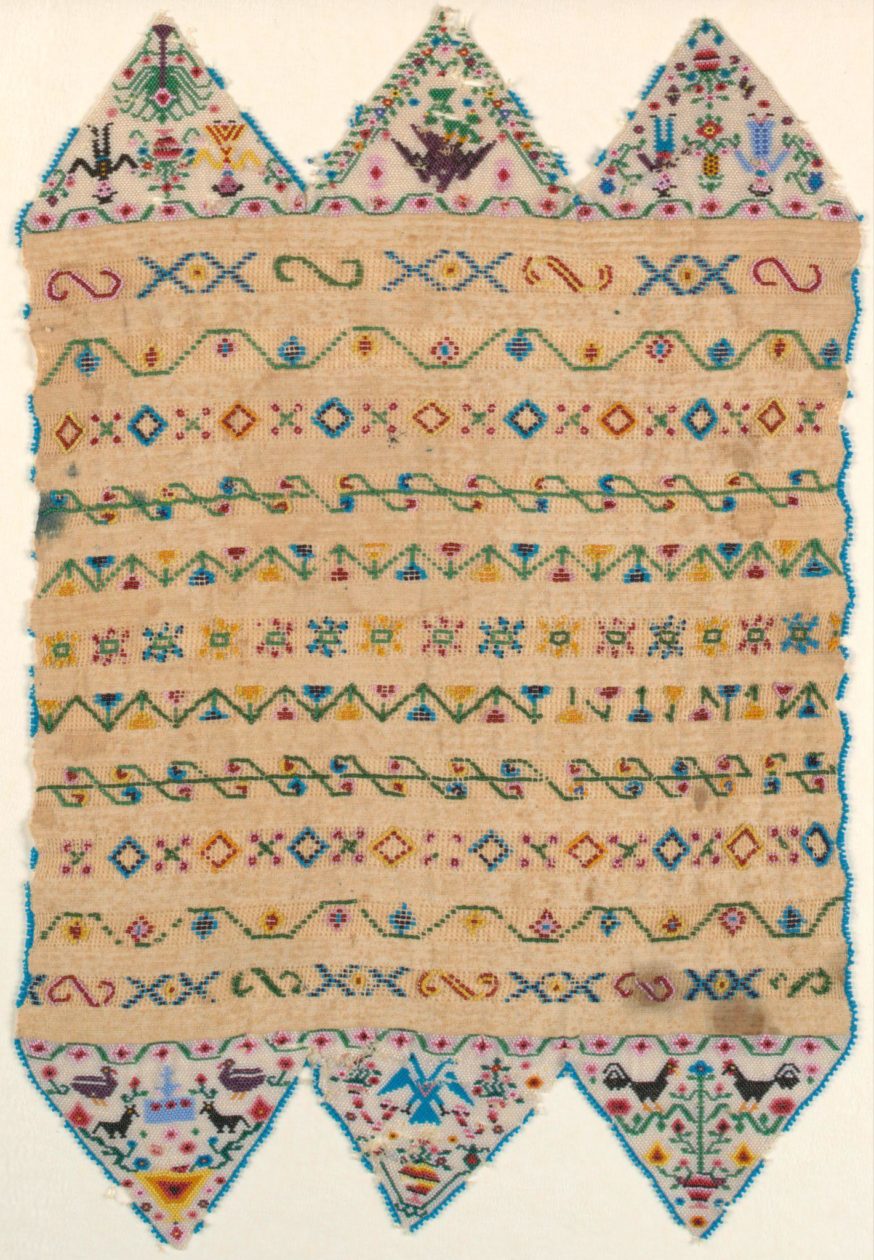

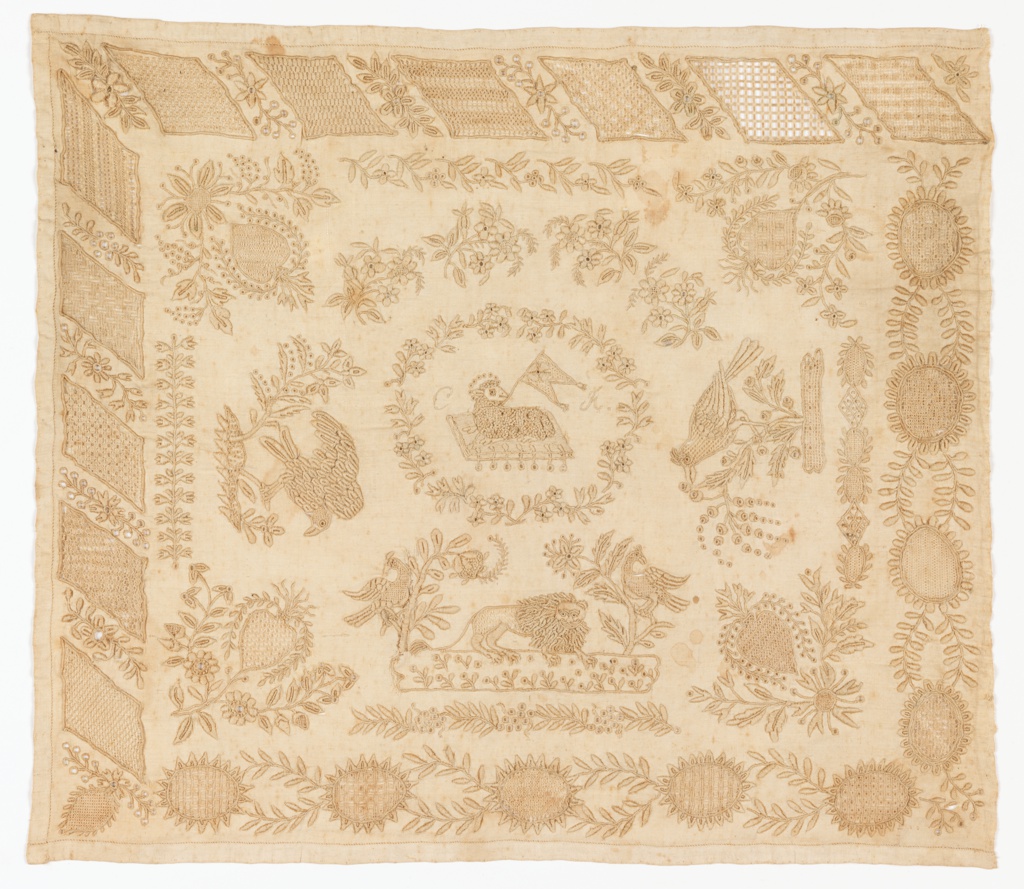

Like samplers made in any country, dechados vary in appearance, materials, and complexity depending on many factors – when they were made, where they were made, who made them, who was providing the instruction, and what type of school the girl attended. In Mexico, socio-economic status was an important factor and until the middle of the 19th century, only daughters born into wealthy Mexican families received the type of education that resulted in the colorful, skillfully worked, silk embroidered dechados associated with the country today. And because Mexico was a Catholic country, the church’s ideals influenced that education. Therefore, in addition to learning needlework, embroidering a dechado was viewed as a means of cultivating the values that the Catholic church wanted to instill in women, such as obedience, patience, and dedication.

Mexico’s history is rich with needlework and textiles, from Otomi to lacework to the cadenilla technique, woven huipiles, chaquira beadwork, and more. What are some of the defining features and motifs of dechados?

Mexico’s textile history is indeed diverse, as are the various dechados made by girls and young women as part of their education. The answer to this question is a primary focus of our presentation and too complex to address in a few sentences.

What stitches and techniques are most commonly used in dechados?

The stitches used on dechados vary depending on where and when the sampler maker is learning embroidery, as well as her socio-economic level and the talents of her teacher.

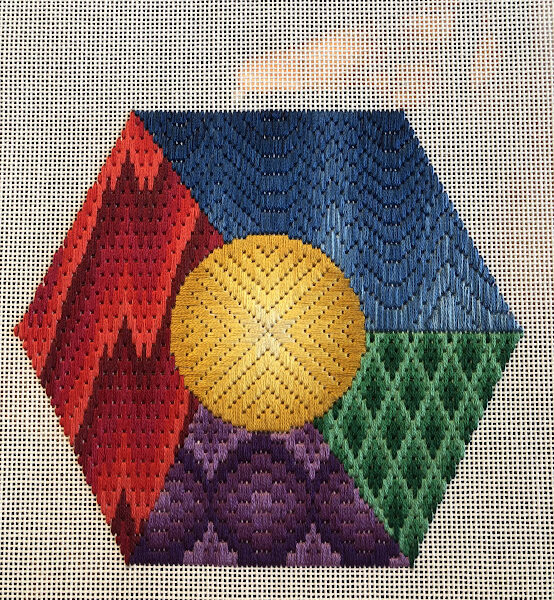

As we will share in our presentation, the early 19th century saw a fair amount of consistency in the stitches and techniques taught in schools for upper-class Mexican girls, as well as the sequence in which they were taught. Some of the earliest and most common stitches practiced by girls creating dechados were punto de cruz (cross stitch), lomillo (long-armed cross stitch), punto atrás (back stitch), punto de satín (satin stitch), calado y vainicas (drawn work) and hilván (running stitch). Some later dechados, however, were created almost entirely in cross stitch.

What materials are most commonly used in dechados?

Up until the middle of the 19th century, most dechados were made of silk thread on linen fabric. Sometimes beads were included. Later dechados incorporated wool and cotton thread, and the ground fabric was sometimes cotton instead of linen.

How are dechados similar to samplers found in other cultures? How are they different?

All schoolgirl samplers, including dechados made in Mexico, reflect the values of Western European culture and the educational expectations of the place and time period in which they were made. In Mexico, the influence of the Catholic church is very clear in comparison to samplers created in other contexts. Transnational influences and governmental priorities also affected the nature of samplers made in Mexico and the longevity of sampler making as a part of the schoolgirl curriculum.

What can an examination of dechados from the 18th and 19th centuries communicate about the history of Mexico?

Mexican dechados reflect the diversity of narratives, lives, and experiences of girls and young women born to families in Mexico. In our presentation we provide a close examination of dechados within the country’s changing historical, educational, and social contexts. We hope to increase appreciation for dechados as artifacts of women’s history in Mexico – and foster an understanding that avoids a homogenized or exoticized vision of Mexico’s history.

Why is your virtual lecture called ‘Este dechado’?

“Este dechado” means “this sampler.” It is one of many phrases girls in Mexico used to take ownership of their work. We used this as part of our title because we focus on specific dechados and reveal what they tell us about one period of female education in Mexico and the girls who spent long hours learning the stitches and techniques to create their girlhood embroideries.

What do you hope needleworkers take from the ‘Este dechado’ virtual lecture?

We hope that people attending our lecture leave with an increased appreciation for girlhood embroidery in Mexico and the many factors that influenced the types of dechados made at different time periods in the country’s history and within different educational contexts.

Thank you to Dr. Anderson and Dr. Flores for providing some cursory insight into the history of dechados.