The title of your virtual lecture presented to EGA is Bojagi, Stitching, and Wrapping Happiness. What is meant by “wrapping happiness”?

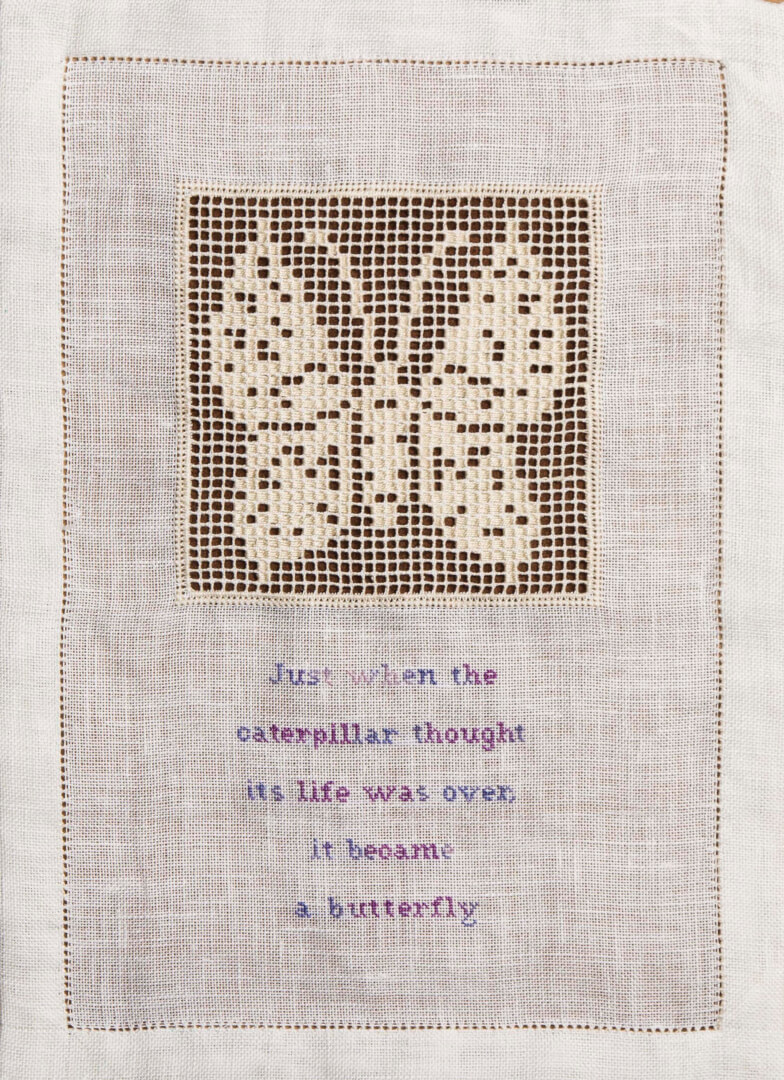

Bojagi, wrapping cloth, is a unique form of Korean textile art. It embodies the philosophy of recycling, as bojagi is made from fabric remnants from other projects. It also carries wishes for the well-being and happiness of its recipients.

When Korean people make bojagi, the idea is that each hand stitch is a wish for something good and happy. Wishing and passing on happiness is part of Korean culture.

When did you first begin crafting bojagi? Who taught you?

My grandmother and my aunt made bojagi and I grew up seeing this tradition, but I learned how to make bojagi when I was in college. I took Korean costume history and construction and bojagi was a part of that course.

You have an MFA in Fashion, studied Clothing and Textiles, and worked as a fashion designer. What drew you back to bojagi after exploring all these different fields? Why did you choose bojagi as your creative medium?

When I was living and working in the fashion industry in Korea, my interest was in western style high fashion. After I moved to California with my husband and my daughter in 1996, I started making bojagi to stay connected to my native culture and tradition. To me, bojagi gives me a feeling similar to that of wearing well-fit clothing. It feels familiar and comfortable.

Has your fashion background influenced your bojagi designs? How?

Yes, my training supported me with knowledge about the materials such as fabrics, construction using hand sewing and stitching, and definitely the use of colors.

Why are bojagi so integral to Korean culture?

Growing up in Korea, I hardly paid attention to bojagi, Korean wrapping cloths, because of its abundant presence in daily life. Bojagi were used as a wrapper, cover, or storage for objects in daily life, special occasions, and religious rituals. Many bojagi were made for practical reasons with specific purposes. The act of making bojagi also carries wishes for the well-being and happiness of its recipients. This labor of love and prayers imbued bojagi with a memory of affection.

How do you begin to choose fabrics to create a Bojagi? What do you look for? What is your design process?

My bojagi creating process is very organic. I choose one element from material, shape, or color. I initiate the process of putting small fragments together, then work as I go along. Sometimes the piece grows as I planned, but other times it grows as if it has its own intention. I just enjoy the rhythm of stitching, with the result beyond my control. I appreciate the beauty that results from the long and slow process of hand stitching – a meditative act that creates an unexpected and spontaneous result.

Are there standard patterns for Bojagi, or repeating motifs?

There are geometric patterns in designs and free form construction that you can build intuitively.

Traditional geometric patterns such as pinwheel, yeouijumun (cathedral window pattern), badukpan (checkerboard pattern), mujigae (rainbow pattern)…

Yeouiju means wish fulfilling jewel, so Yeouijumunbo can be translated as a jewel pattern bojagi. Sometimes it is called Gojeonmun, or old coin pattern. The mun was an old coin in Korea that had a circle shape with a hole in the middle. Yeouijumunbo is one of the jogakbo designs that is often found in the Joseon dynasty period (1392-1910).

The first documented evidence of the Cathedral Window design used in a quilt appeared at the Chicago World’s fair in the US in 1933. In her book, Cathedral Window Quilts, Lynn Edwards made the inference that this technique might have been brought by missionaries from the East in the early 20th century.

Bojagi are striking examples of abstract expressionism. Why do you think Bojagi lean towards the abstract rather than the figurative?

Using limited resources, oftentimes due to recycling scraps, people have to create utilitarian and eye pleasing designs. I think this constrained condition encourages creativity.

Do you have a daily/weekly/monthly practice that you’d recommend to other embroiderers interested in honing their craft?

When I feel that I am in a creative rut, I pick up a very simple project or stitches which don’t require much thinking. The repetition of the simple act of stitching helps me to recharge my creative energy.

What embroidery or color trends are you drawn to this year?

I am working on a plain woven white cotton with my father’s calligraphy practice paper to create a work that combines my effort with materials from his past. It is very plain in color, but the work uses a delicate design and precise technique. I am quite happy with the progress so far.

What do you hope attendees take away from your lecture on Bojagi?

As I always emphasize, I wish to extend happiness when I teach bojagi, and I hope attendees can feel my wish for happiness imbued in the long and slow process of crafting bojagi.