Jenny Adin-Christie

This profile of Jenny Adin-Christie originally appeared in the December 2017 issue of Needle Arts magazine.

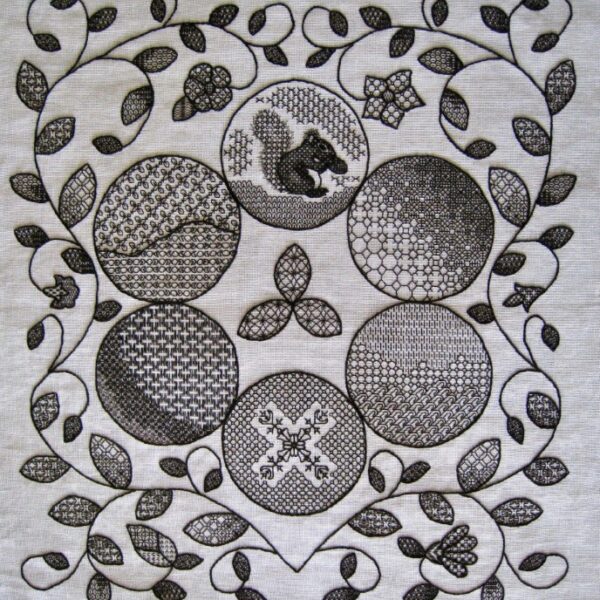

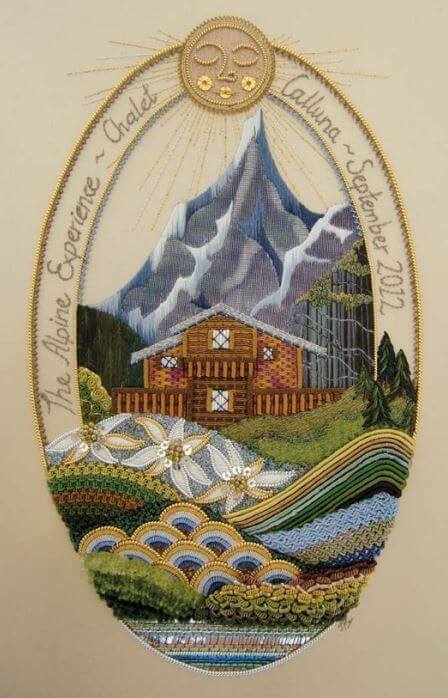

Jenny Adin-Christie’s work is exquisite in every way. From precise execution to thoughtfulness in design, each work is carefully conceived. Her work stems from eclectic interests. She works in a variety of techniques, and although she specializes in whitework, raised work, and metal thread embroidery, her real delight is in combining them, “to push fabrics and threads to see what they can do.”

Although inspired by embroidery of the past, Adin-Christie strives to create new methods and techniques. “Embroidery should never stand still,” she asserted. “It should always look forward, inspired by its heritage.” She draws on her own experiences and extensive training in embroidery, art, and design.

A trained apprentice from the Royal School of Needlework (RSN), Adin-Christie currently works freelance, traveling internationally to teach, tutoring private students in the United Kingdom, and working private, royal, and ecclesiastical commissions from small pieces to large works that include appliqué and machine embroidery. She was a member of the RSN team who made the lace for Kate Middleton’s wedding gown (the details of the process must remain a secret for thirty years).

Recently, Needle Arts had the opportunity to interview her. Her answers to some of our questions follow.

How did you come to focus on whitework, raised work, and metal thread embroidery?

On whitework

My love for this form of embroidery began when I was an apprentice at the RSN. My love for whitework began while stitching the fine whitework piece that is considered to be the culmination of the first two years of training of this three-year course. I was struggling at the time to master the balance between slightly obsessive perfectionism and working to speed, an essential balance for the professional embroiderer. When working white on white, I found that the lack of color meant that I had to focus only on stitch and texture. I had fewer decisions to make. Consequently, I began to speed up. Gradually, I conquered this balance, but it took years.

I love the extreme intricacy of whitework and the way it exploits every aspect of embroidery and fabric, from laying stitches on the fabric surface, distorting and adapting the weave of the base fabric, to cutting holes in the base fabric to reveal the world beyond. It has great scope for creating depth and life. Whitework should be one of the first things an embroiderer learns, to learn how to handle the stitches beautifully without the distraction of color. If you can portray a design clearly in white on white, then color comes easily.

For the past fifteen years, I have taught whitework to many students at the RSN and have developed a system for teaching, not so much the individual forms of whitework, but how to look at the key stitches which span the whole spectrum of whitework. I teach these stitches as a tonal scale: working from those which add the greatest depth, height, and whiteness to the ground fabric, such as raised and padded satin stitch; to counted satin patterns and surface stitches, such as fishbone, feather, fly, and knotted stitches which add a little whiteness to the fabric; to pulled work which begins to open up the surface and lets the color behind the fabric peek through; to drawn work and finally to open work, gradually revealing even more of the color behind. Looking at all whitework stitches within this tonal scale goes beyond classic domestic petticoats and table decorations, and allows for effective design of pictorial pieces with tremendous depth and life.

One of my greatest whitework moments was when I worked a fine whitework panel based on the architecture of London’s Natural History Museum, for the RSN’s 2003 Leighton House exhibition, which raised funds for the RSN. This piece sold for close to £5000, about $8,500 US, and I was delighted that someone was willing to pay such an amount for a piece of whitework, which is often classed as a rather lowly domestic form of embroidery.

I have also always had a great love for the work of Lady Evelyn Stuart Murray of Blair Atholl, Perthshire. She was rather obsessive about her love of whitework, as am I. She collected antique pieces, and copied them to learn stitches, as I do. She worked the most incredible piece of whitework in existence, the British Arms, on glass cambric. It is truly astonishing in its accuracy and exquisite mastery of the craft. Her work is endlessly inspiring, as is the Ayrshire work produced in nineteenth-century Scotland.

On raised work

My love of raised work, particularly that of the seventeenth-century, began when I was seventeen and attending secondary school in Ashbourne, Derbyshire. I was working on my General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) in textiles. As usual, I was rather obsessed with this work as I loved it so much. I could do the academic subjects, but textiles were my love. The school

found merit in my work and allowed me to convert my GCSE to an A-Level, the two-year study that universities in the United Kingdom use to assess qualifications for a degree course. I was very lucky because the following year, the textiles A-Level disappeared from the curriculum, and I wouldn’t have been able to pursue it. My life may well have gone in a very different direction.

While working on my A-Level, I visited the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) for the first time. I was overwhelmed by this utterly amazing building, full of incredible embroideries, textiles, and other treasures. I saw the raised work caskets for the first time, and surely, like all those who have seen these pieces, fell in love with them for their intricacy, storytelling, and magnificent array of stitches, and for the fact that they were worked by such young hands.I set out to make a casket based on what I saw in the V&A. My father made a beautiful wooden casket for the panels I worked. Looking back, I didn’t know many stitches, and it seems a poor comparison to the pieces that inspired it, but I loved every minute of working it. At the time, the raised embroidery books by Barbara and Roy Hirst had been published, and I taught myself many techniques from them.

Since then, I have continued to research seventeenth-century raised embroidery, endlessly studying antique pieces for inspiration. However, I use these as a source of stitches and techniques. I do not render them in their original form in my own work. Raised embroidery reached a peak at this time and should not be copied. Instead, I like to create my own designs and techniques based around raised work, reinterpreting old methods, having new threads made for use, and combining them with fabulous modern materials, which gives a whole new lease on life to the work.

On metal thread embroidery

Metal thread embroidery has inspired me since I worked my piece of Coronation Goldwork as a RSN apprentice. I loved the precision, intricacy, and rich history of goldwork. During my apprenticeship, we had the coronation train at Hampton Court for exhibition. It was stunningly beautiful. I feel honored to be part of this heritage of RSN training which trains embroiderers to work to the standard required by such important state pieces and to work seamlessly as a team to create them. Metal thread is unlike any other form of embroidery, for it combines so many skills and tools beyond the basics.

Will you describe an event that epitomizes your experience at the RSN?

One of the most memorable experiences was creating the new All Seasons and Lenten altar frontals for Canterbury Cathedral and managing the studio team. I was thrilled when my design was chosen by a national organization. After many years, it was the first major RSN embroidery designed by faculty member. We were always creating other people’s designs, but it was super to encourage broader appreciation not only for our stitch skills, but for our design skills as well.

The opportunity to combine design and stitching is a true example of what the training provides. The RSN motto was originally “Small Birds May Fly High,” describing how the original school enabled disadvantaged young women to support themselves by learning embroidery and to have a fulfilling professional career.

This motto applies to me, too! If I hadn’t had the chance to be trained there, I wouldn’t have the satisfying, stimulating, and enjoyable career I have now, which has given me the chance to experience the most marvelous things. I am currently writing in the rainforest in North Queensland, the result of being invited for my fourth teaching trip to Australia. I’ve also taught in New Zealand and the United States. I’m looking forward to teaching in Canada in 2018. Little did I know that embroidery would allow shy, small birds from little country towns to fly so high! This experience is the inspiration for my Wren Etui in raised work.

How do you approach design?

Most ideas for my work come out of my head. In the rare times when I am not working—during a bath, the walk to pick up my daughter, or the times of monotonous stitching, or in the depths of the night—my brain spirals with ideas! Hence, the notebook travels everywhere with me so I can record my ideas. I see everything in stitches. A good design for embroidery is drawn and developed with stitches and fabrics in mind. I am always thinking of the stitches and textures as I draw.

When I design commissioned pieces, the first step is to visit the place where the embroidery will sit. Inspiration comes from the environment, architecture, and the feel of the place. Often, the instinctive initial design sketches will evolve into the final piece. I won a commission for an altar frontal commission because I asked to see the church before I started designing. The other designers sent designs without seeing the church interior. It is essential to fit the design to the space.

I break down a design into the elements of the whitework tonal scale before I add color. This helps me to think through the essential elements and principles of a successful embroidery design, including height, texture, contrast, and depth, and thereby create a piece that will draw the viewer into its magic. Good embroidery design will survive the ages to be revered by generations to come.

Can you talk about the commission for Sir Paul McCartney’s album cover?

Sir Paul McCartney asked us to work individual letters and a linked monogram of ECM, which stands for ecce cor meum, the title of his classical work. It was fabulous that he wished it to be hand-embroidered in the traditional style rather than digitally generated.

At the time, I was managing the project in the studio and had run out of appropriate slate frames! As my flat mate, who is also an RSN apprentice, was away, I borrowed her slate frames for the job. The completed stitching had to be sent to the publicity company for photography. Apparently, Sir McCartney loved the work as it was, still laced on the slates. He kept them to hang on his wall! I had to confess to my friend where her slate frames had ended up!

What have you learned from your experience?

To earn a living as a professional hand embroiderer, it is okay to compromise obsessive perfectionism. It also results in work with much more life, energy, and movement. I see so many students struggling with this same mental battle! Magnifiers and unpicking can be a curse of the perfectionist mentality, so magnifiers should be avoided whenever possible. Using them can lead to stagnant work. Use them only if you need magnification to see. Look at your work as a whole rather than under this tiny field of vision. The more relaxed you are as an embroiderer and the less you unpick and analyze, the better you will stitch.

Adin-Christie is passionate about creating new embroidered works and about passing on her skills. Her plans include writing and exhibiting her work and her students’ work. “My students produce amazing work, and I would love to celebrate it publicly,” she said.

One week while working the altar frontal for St. Mary’s Church in Beaconsfield, U.K., she took it to the church and invited the congregation and local schools to put a stitch into it. People from age five to ninety took part. “This gave such a tremendous sense of ownership and understanding to the community,” Adin-Christie said. “When the piece was dedicated, it was super to see everyone looking for their stitch. Several people said how therapeutic and inspiring the experience was. If I can inspire others to gain enjoyment from stitching as I do, this is a great thing!”

To book a teaching engagement with Jenny Adin-Christie, visit her website at www.jennyadin-christieembroidery.com or contact her at jenny.adinchristie@gmail.com. View comprehensive, handillustrated instruction manuals and a broad range of beautiful, specially sourced materials from around the world, including bespoke handmade items; a range of threads which she orders specially made, embroidery tools crafted by her father, and other unique items such as wooden boxes and haberdashery.

Profile by Cheryl Christian, Needle Arts Editor

Jenny Adin-Christie's Tips for Technique

Read some tips from Jenny on

whitework, raised work and metal thread techniques.

Needle Arts Magazine

Our quarterly magazine is one of the benefits of being an EGA member, come join us on the link below. Past issues of Needle Arts are available for purchase.