Tanya Bentham has studied and worked with medieval embroidery stitches and materials for most of her adult life. She’s written three books on medieval embroidery and opus anglicanum, hosts a private opus anglicanum Facebook group, and shares medieval embroidery kits and coursework via her website, opusanglicanumembroidery.com. We were delighted to sit down with Tanya ahead of her lecture at EGA, My Work in Medieval Embroidery. You’ll find Tanya’s interview as humorous, witty, and irreverent as the medieval embroidery she holds so dear.

Tanya Bentham has studied and worked with medieval embroidery stitches and materials for most of her adult life. She’s written three books on medieval embroidery and opus anglicanum, hosts a private opus anglicanum Facebook group, and shares medieval embroidery kits and coursework via her website, opusanglicanumembroidery.com. We were delighted to sit down with Tanya ahead of her lecture at EGA, My Work in Medieval Embroidery. You’ll find Tanya’s interview as humorous, witty, and irreverent as the medieval embroidery she holds so dear.

How were you introduced to embroidery?

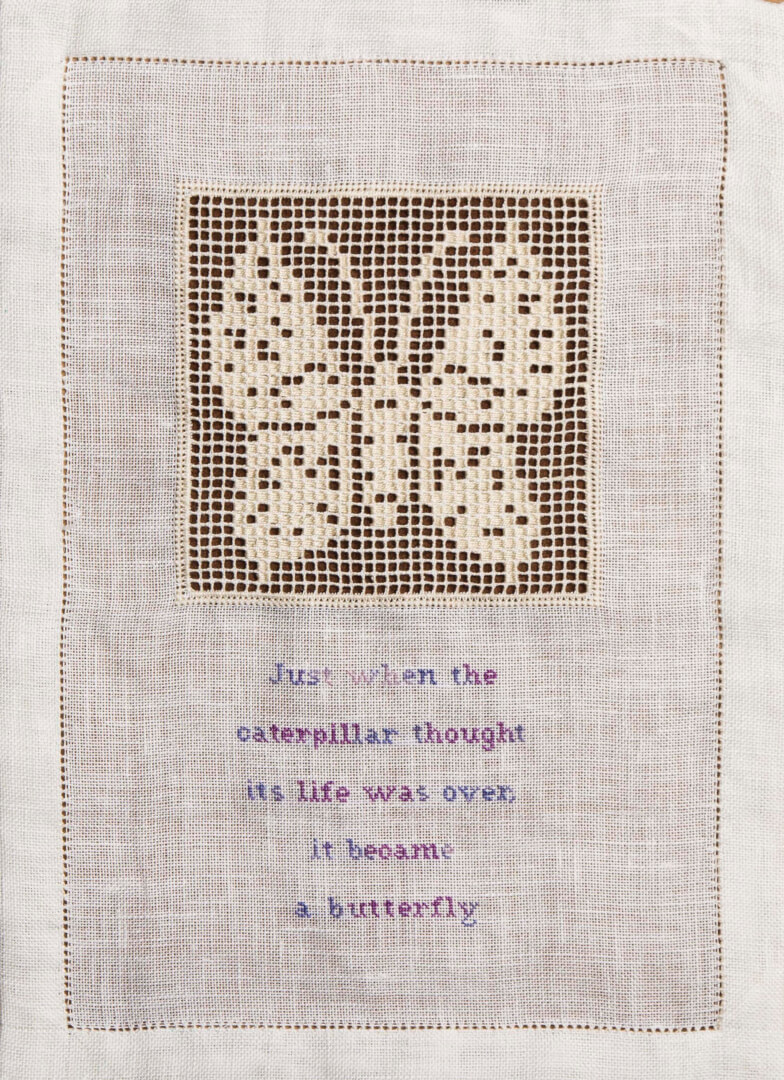

We did cross stitch at primary school, but I’m not from a family of embroiderers or anything. I began making medieval costumes when I was about fourteen or fifteen, and it just sort of grew out of that, really. Not that I didn’t produce some really terrible stuff at that age, mind you—there was a lot of four-ply wool and crochet cotton involved because I was a kid and skint, but it was all part of learning, everyone has to start somewhere. I’m a firm believer that anyone who never made a mistake never made anything.

What drew you to medieval embroidery?

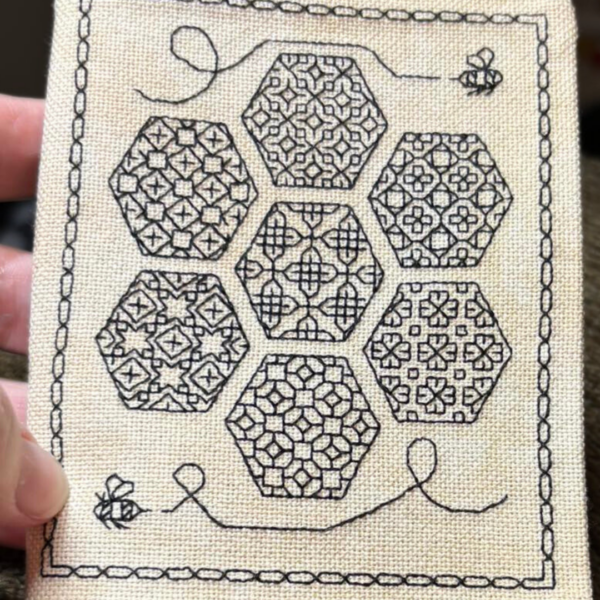

I love the silliness of a lot of medieval imagery, and also the beauty—the two are not mutually exclusive. Plus, I like the sophisticated simplicity of the style of stitching. A lot of later historical embroidery is about knowing a hundred stitches and showing how clever you are by using all of them at once, whereas medieval embroidery uses only two or three stitches at once, but often uses them in a way that speaks of intimate mastery of technique—it’s not as showy about its cleverness.

Why was it important to you to use materials, fibers, and fabrics authentic to the medieval period in your recent class Laid and Couched Work Dragon?

Certain techniques work better with the right materials. Medieval techniques just tend to work best if you use the correct materials. Laid and couched work wool works best because it fuzzes a little and gives good coverage. When I work areas of laid and couched/bayeux stitch in filament silk as part of the opus anglicanum technique, it takes a lot more effort to maintain smooth coverage because silk doesn’t forgive so many sins. On the other hand, when doing opus is just has to be silk, and very specifically filament (aka flat or reeled) silk, because opus is all about manipulating light, and no other fiber brings light into the work in same way—even a spun silk doesn’t work for opus, to the extent that I’m adamant it’s NOT opus unless you use the right silks. I think saying you’ve done opus anglicanum when you’ve done it in cotton is like saying you learned to swim in your living room—you might know the theory, but you’ve missed the point.

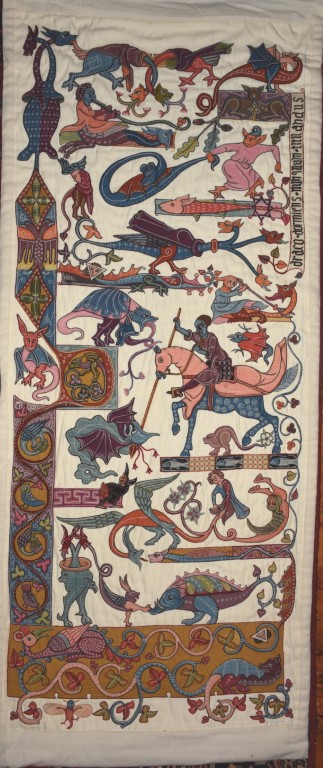

Tell us a little bit about the “Bayeux Dragon.” Where did you find inspiration for this particular design?

I call him Mickey, because he looks as though he’s wearing Mickey mouse ears to me. He is a piece of marginalia from the Luttrell Psalter, and I originally used him as part of my Luttrell Dragon Fantasy, a two-foot by five-foot hanging in laid and couched work that draws various dragons from all over the Psalter and weaves them together into a larger piece. I didn’t actually choose him for the class; Heather Keiko Long, an EGA member, talked me into the class and chose him for me!

You sometimes combine contemporary designs with the medieval embroidery techniques and aesthetics. Where do you find inspiration?

Usually in medieval tales and images. Every generation looks at the past from its own perspective and inevitably projects, rightly or wrongly, its own views and morality upon the past. I just play with that. It’s easiest with humorous images because there’s a certain shock value at first in realising that our ancestors also enjoyed a good fart joke, but then it becomes a connection with the past because we still laugh at fart jokes. Well, I do, at least, but then my sense of humour is particularly puerile.

What does your design process look like?

I have an idea, maybe I discuss it with my partner, Gareth, who has all the artistic abilities of a house brick (not that he’s stupid, he just has a brain that is almost completely analytical to the point of excluding imagination, whereas I’m all imagination and no sense).

So many of your designs feature vivid color pairings. How do you approach marrying and using colors in your design work?

The wools I use for design and teaching are naturally dyed. One of my big pet peeves is when people do replicas and carefully match their threads to the current colors of the originals, thinking that all colours were muted in the past. They weren’t. Color was expensive, yes, but that made it all the more joyous and important. I have spoken before about how liberating it is to use the restricted palette imposed by natural dyes (I don’t use hedgerow stains like cabbage, I stick to woad, weld, madder, and the like, plants which were deliberately cultivated for their color). Sticking to a narrow range of colors made me start looking more widely at color in medieval art and I began to realize that the restriction leads to a rhythm and harmony of design. If you throw all 200 shades from your workbasket at one small piece of embroidery it will look like a rainbow vomited on your canvas, but if you use the same blue over and again in six different ways throughout the composition it becomes harmonious. By the same measure, if you want something to really stand out, maybe draw focus, use the bright red there and only there.

Do you have any favorite tools you can’t live without?

Not really. I buy needles in bulk packs of 1,000, and I have six of the same embroidery frames because it works for me. I have a stiletto I use occasionally, but if I lost it I could use a darning needle. I also have an unreasonable number of scissors, but that’s largely because my cat will always sit on them, so I need at least three pairs at once. I have a weird little pair of black plastic tongs that really do clean my glasses every bit as well as the advert said they would. I use those every time I sit down to sew—do they count?

Do you have a daily/weekly practice that you’d recommend to other embroiderers interested in honing their craft?

Stitch every day. When you find a technique that feels right, stick with it. I intend to spend the rest of my life exploring the possibilities of medieval embroidery; it’s chewy and has endless potential. There is great pleasure in mastering one thing, I think trying to be Jack (or Jill) of all trades seems a stressful thing—I still feel I can spend a lifetime exploring the intricate possibilities of medieval stitching, especially opus. Trying to learn canvaswork or modern goldwork would just be a distraction from honing that.

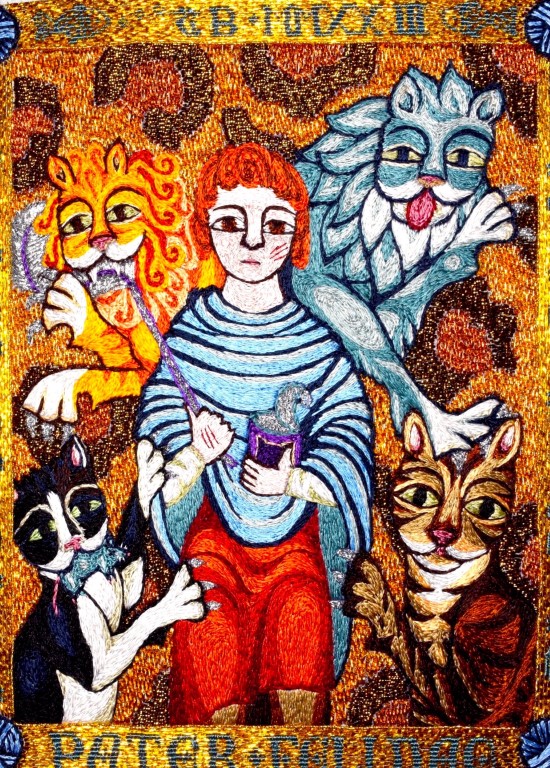

Do you have a favorite embroidery design from your portfolio?

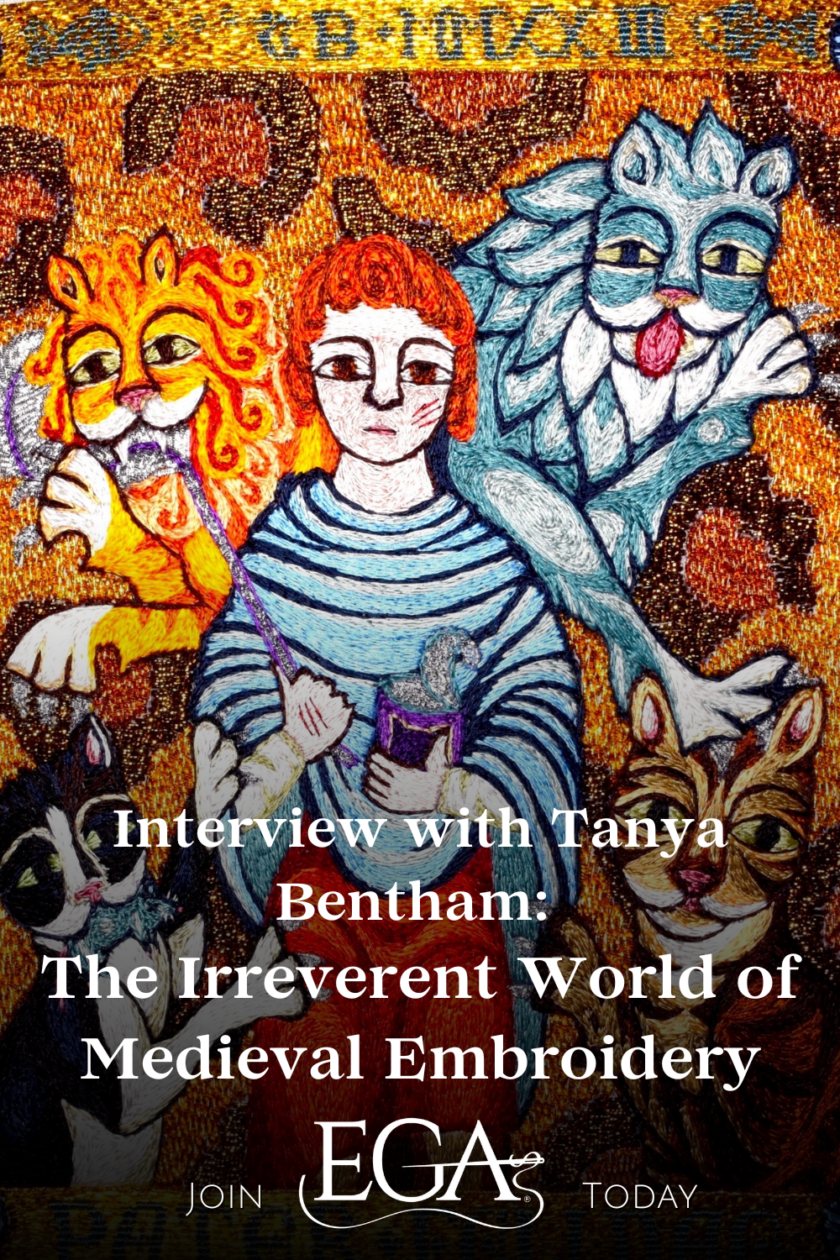

It changes from week to week and project to project. Cat daddy will always be a favorite because it’s really personal. A few years ago there was an article in the Sunday Times about the restoration work at Lincoln cathedral, featuring the relief sculpture of Daniel in the lion’s den. We were reading the paper in bed, and I nudged Gareth and said, “that’s you, that is”. The idea brewed for the statutory six months or so, then I worked the design as opus, making Daniel ginger like Gareth, and giving him a feather toy and can of catfuds, the lions became my Maine coon, Branston, his Bengal, Trubble, little black and white Sam from next door, and a random ginger to represent that cat who will inevitably follow Gareth home one day and say “I live here now” to which Gareth will respond “and which of these six gourmet catfuds would sir prefer…?”

Do you have any projects or events coming up we should keep an eye out for?

There are things in the pipeline, but I’m not sure which ones I’m allowed to talk about. I’m thinking about putting together a proposal for a second opus book, but that will be a few years in the writing, and I’m starting to film a new online class for my website.

Your lecture is sure to introduce a new obsession for many embroiderers interested in the medieval style. Where can they find further inspiration, guidance, and community?

I have a Facebook group called Opus anglicanum medieval embroidery, they’re a friendly lot. And of course there are my books, Opus Anglicanum, Bayeux Stitch, and Naughty Medieval Embroidery.

Discover more from Embroiderers’ Guild of America

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.