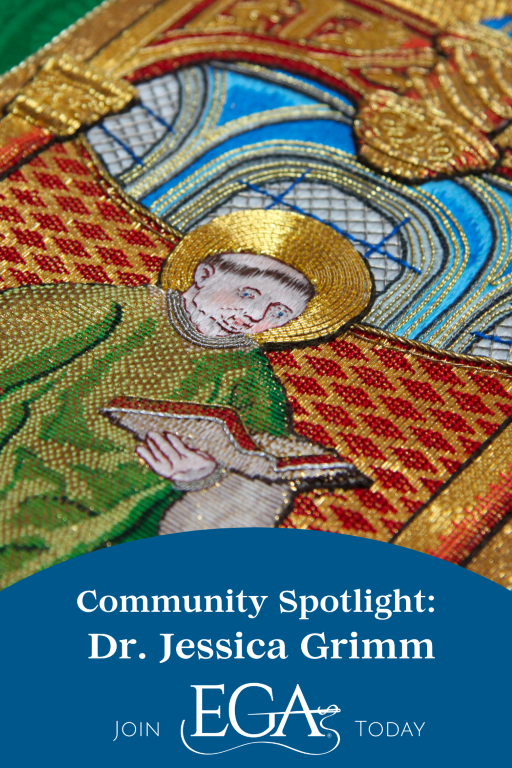

EGA is delighted to announce a new feature on the EGA blog: Community Spotlight! Community Spotlight aims to highlight a different artist and raise awareness around the many talented needlework artists contributing to the needlework community.

This month, we sat down with Dr. Jessica Grimm, also known as Acupictrix. Dr. Grimm is a member of our Daylilies Chapter in the Great Lakes Region who writes a fascinating weekly blog on medieval goldwork embroidery. As a RSN-trained embroiderer with a doctorate in archaeology, Dr. Grimm occupies a unique vantage point to study and share the history behind medieval goldwork. Keep reading to learn why her diverse background makes her specially suited to this particular research arena, how medieval goldwork embroiderers employed clever techniques for hiding their ends, and much more!

Your website, Acupictrix, is dedicated to medieval goldwork embroidery? What drew you to this needlework niche?

When I started my blog about 10 years ago, it documented my story as an embroiderer trained at the Royal School of Needlework embarking on a new career as an embroidery tutor. Over the years, I became more and more specialized towards historical embroidery techniques. After seeing an epic exhibition on medieval goldwork embroidery in my native Netherlands, I found my calling.

What is the meaning of “acupictrix”?

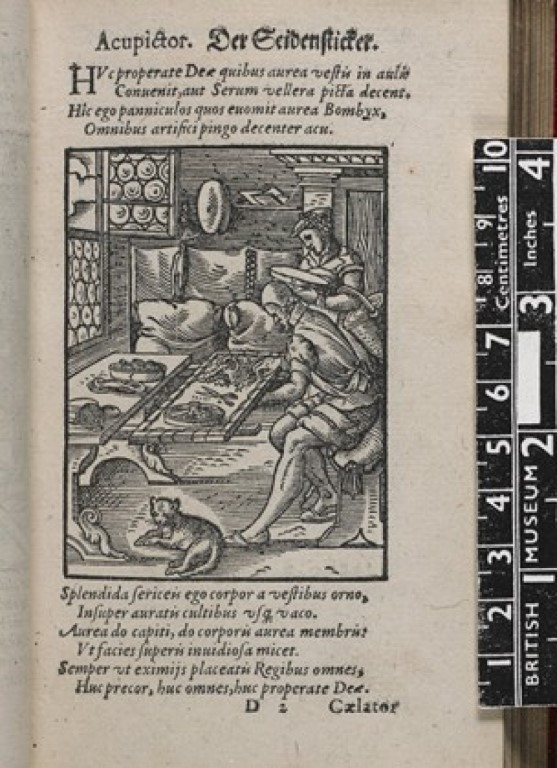

Original medieval sources are often written in Latin. The name for a male embroiderer is acupictor. Literally: painter with a needle. The female form, as far as I know, absent from the documents, would be acupictrix. That’s how my company name was born.

© Trustees of the British Museum, acc. no. 1904,0206.103.27.

You have a doctorate in archaeology. How does your educational background inform your research into medieval embroidery?

For my doctorate, I analyzed the medieval animal bones from the German port town of Emden. The Middle Ages have always fascinated me. In a way, they are familiar to us, but they can be quite exotic too. Collecting data and squeezing statistically valid answers from them, as well as telling stories, is what I learned during my archaeology study. Knowing how to conduct research and how to evaluate sources are valuable trades I was taught at university. Also, in some parts of Europe, there is a strong division between people who work with their brains and people who work with their hands. With my background in both academia and needlework, I am increasingly able to bridge that gap.

Do you have a favorite example(s) of medieval goldwork embroidery?

That’s like picking a favorite child. Some pieces impress because of their sheer size. The embroidered surface is simply so large that you are immediately in awe of the hours spent to achieve this. Other pieces are technically very stunning. Especially those worked in high-end or nué (shaded gold). And then there are the pieces that are downright ugly to most. They come from archaeological excavations, mostly in churches (think opening tombs). They are small, discolored and often brown fragments. But the fact that they can be over 1,000 years old makes them instantly dear to me.

Utrecht, Jacob van Malborch?, ca. 1505-1515

Museum Catharijneconvent, Utrecht, foto Ruben de Heer

A piece I like very much is this cope hood made around 1505-1515 in Utrecht, the Netherlands. It is one of the very few pieces that can be tentatively linked to embroiderer Jacob van Malborch. The guy with the blue clothes at far right looks us straight in the eye. Painters often added themselves into commissions as a bystander figure. Maybe this is Jacob the embroiderer himself…

What are some defining characteristics of medieval goldwork embroidery?

The simplicity of the goldwork techniques and materials used. There’s normal surface couching, underside couching and simple silk embroidery (brick stitch, split stitch, stem stitch, satin stitch/laid work, and knots). It is all worked with passing thread and flat silk. Sometimes, fresh-water pearls and (shaped) spangles are added for embellishment. Many pieces also have some sort of padding going on. From very simple string padding to full-blown stumpwork pieces at the end of the medieval period. With these simple and limited ingredients, almost all medieval goldwork embroideries can be made. For instance, several strands of passing thread can be combined into all sorts of twists.

Museum Catharijneconvent, Utrecht, foto Ruben de Heer

A good example of how relatively simple stitches can result in very high-end medieval goldwork embroidery is this detail of an orphrey made in Amsterdam between 1520-1529 (above).

You’ve made numerous discoveries, detailed in depth on the Acupitrix blog. What are some of your most exciting discoveries?

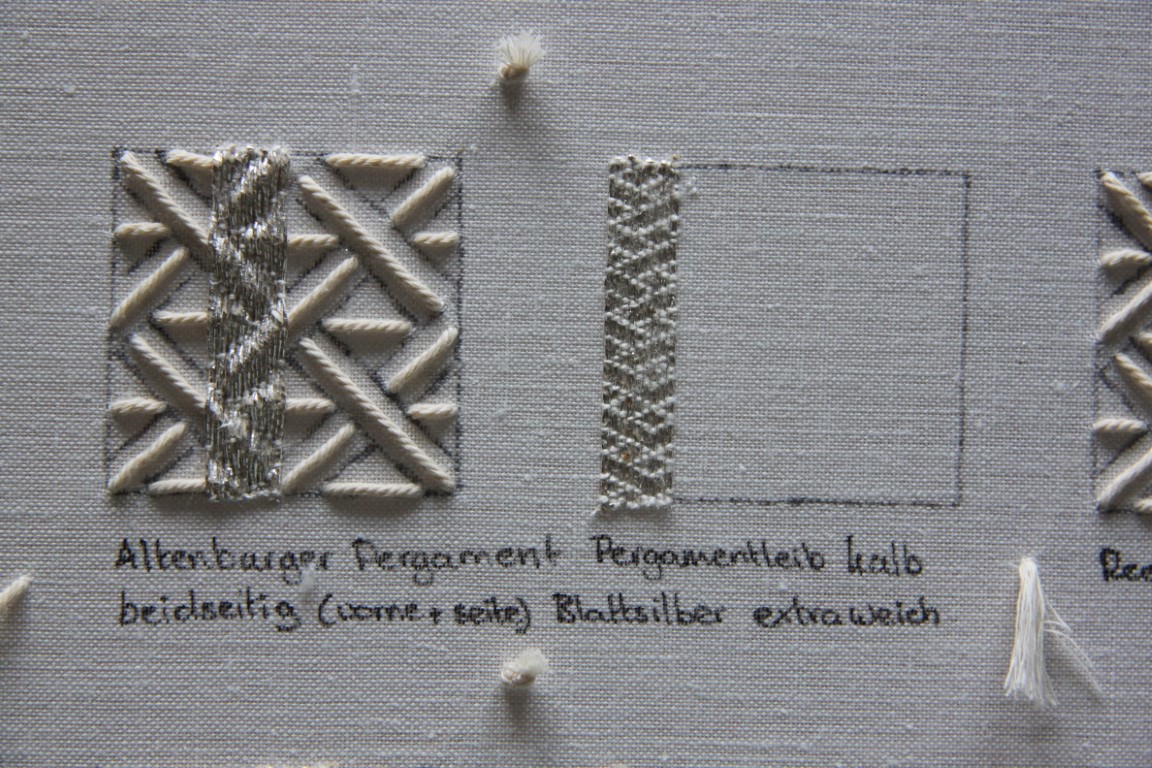

When I was asked by fellow archaeologist Dr. Katrin Kania to test her recreated membrane silver threads, I was over the moon. Membrane gold or silver threads were made by gluing a very thin strip of gilded silver or silver to a strip of animal gut. This strip was then spun around a linen or silk core to make the gold or silver thread. The exact process has been lost to us. So to be asked to stitch with the first batch of membrane silver in a couple of hundred years was something very special indeed (see below).

You’ve learned a lot from museum archives, online catalogs, and by visiting embroidery exhibitions. But one imagines there are certain things that can only be discovered in the act of doing. What are some of the things you were only able to learn by physically attempting a recreation?

When you work from pictures, it is often difficult to get a feel for the size of the actual object. The quality of many medieval embroideries is achieved through the fineness of the materials used. Getting my hands on fine enough materials and figuring out how to best combine gold thread and silk is something I can only achieve by making a sample and comparing it to the original.

You engage in a lot of embroidery recreation when analyzing medieval goldwork embroideries. Why do you recreate certain pieces, and what are some of the challenges needleworkers face when attempting to recreate a medieval embroidery? Do you have a favorite recreation?

When I did my first recreation (the orphrey of St Laurence), I was simply curious if I could pull it off. I was not at all concerned with using appropriate materials. Over the years, I have started to work on samples of unusual pieces. For instance, how does one do bead embroidery on parchment? Or when I read something written by a curator that does not seem right from the perspective of an embroiderer, I start to make a sample.

Finding the right materials is the hardest thing. For instance, the cut of real stone beads has changed and is not comparable to medieval beads. As mentioned, membrane threads are no longer available. But also, modern passing threads behave slightly differently from the medieval original. Using ‘real’ gold threads (gilded on a pure silver base with a silken core) already comes closer to medieval threads than our standard gilt threads. But they are much more expensive.

Another challenge is that we rarely can inspect the back of the embroidery. This is especially important when you want to know if gold threads were being plunged or if they were simply oversewn on the front. The medieval embroiderer was very clever in hiding the end of his gold threads under subsequent embroidery so inspecting the back is often your only option.

Although St. Laurence has its flaws when it comes to using the correct materials, I think I like him best.

You are currently compiling a database of medieval goldwork embroidery from Europe. How did you begin discovering works for this project? What is your goal for the database?

This will keep me busy till the end of my days. Naively, I thought that there would be a limited number of surviving pieces and my database would be quickly complete. It turns out that there is much more material than one might think. As needlework is undervalued in art history, there is no complete overview of medieval goldwork embroidery. There are a few regional studies, but not even proper links between them. Also, many of these regional studies are older and new pieces have come to light since.

My database will hopefully serve as a starting point for future research. I am already able to point researchers, antique dealers, and priests in the right direction when they want to know more about a particular piece they have acquired. A lot of medieval goldwork embroidery was being mass-produced. This means that the same designs were used over and over again. Finding these ‘‘Doppelgänger’ is my specialty.

Another important thing is to find fragments of the same embroidery that have been dispersed over several museums. Collectors in the 19th century routinely cut up pieces so everyone could have a piece for their private collection. These collections were mainly started as inspiration for modern pieces (Gothic revival). This week, I found a further fragment of a famous 13th-century embroidery from Aachen Cathedral in the online catalog of a Dutch museum.

If needleworkers had just one book to read about medieval goldwork embroidery, which book would you recommend to them?

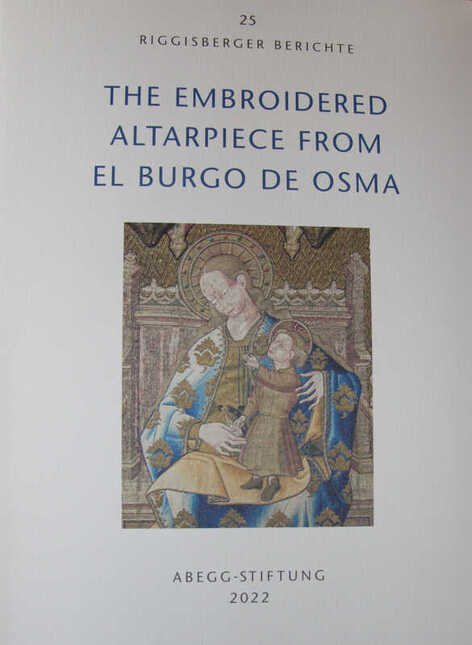

It is a publication by the Abegg Stiftung. In my opinion, their publications are the gold standard when it comes to textile research. Unfortunately, they mainly publish in German. However, as the El Burgo de Osma altarpiece is housed in the Art Institute of Chicago, this one is in English. It includes lots of detailed pictures and descriptions of the embroidery techniques used.

What are some exciting projects and events you have planned that you would like to share with needleworkers?

My main goal for the coming years is to try to teach where the original pieces are housed. I like to be able to show my students the medieval originals whilst they are working on a recreation. This year will see me teach at the Treasury of Halberstadt Cathedral again. This museum houses one of the largest medieval textile collections on permanent display in the world.

I am also teaching a 10-week online course for Medieval Goldwork Embroidery. More information and registration details can be found here. For those who follow me on Patreon at the Master tier, I will also be conducting a free Medieval Embroidery Study Group. We meet once a month on Zoom for a lecture focused on a piece of embroidery I’ve seen in a museum, with a subsequent Q&A afterwards. Interested needleworkers can access all of my upcoming classes and events here.

Thank you to Dr. Jessica Grimm for providing this illuminating peek into her adventures with medieval goldwork embroidery! We encourage EGA readers to sign up for the Acupictrix newsletter to stay updated on her work.