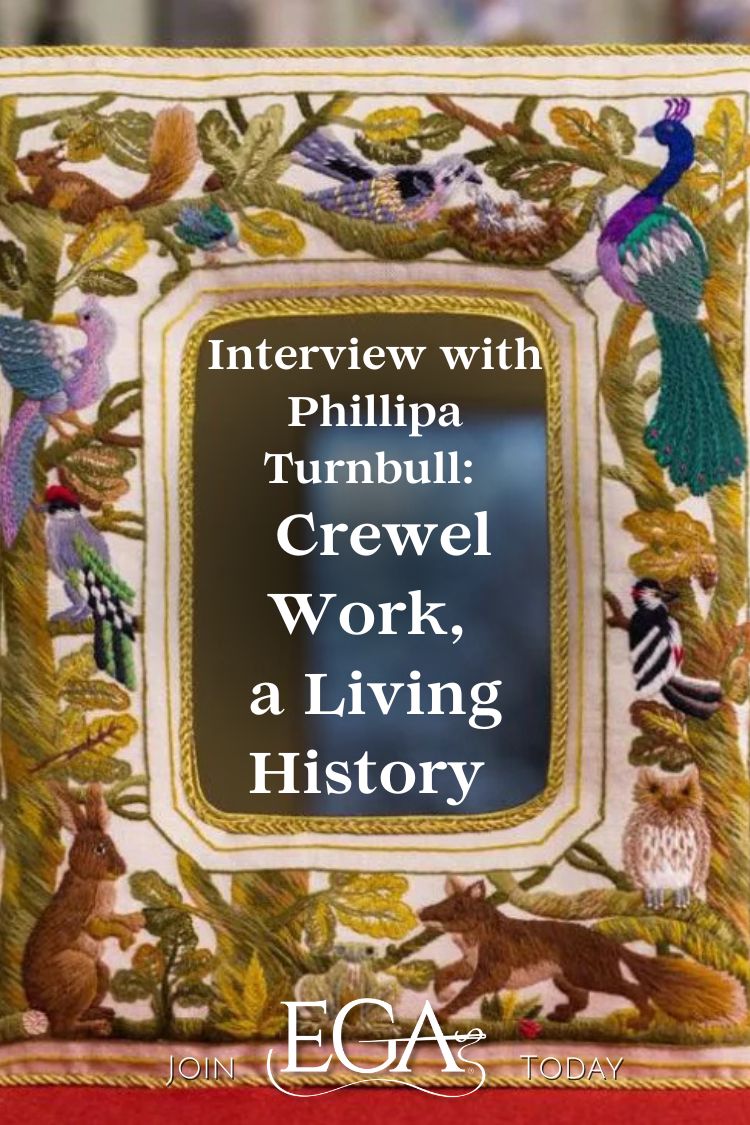

Phillipa Turnbull’s upcoming virtual lecture, A Timeline of British Crewel Work, explores the history of crewel work and its reflection of British culture. Phillipa describes crewel work as “forgiving and joyful,” and admits she only came to the art as a means to avoid an “ancient Singer sewing machine.” In this illuminating and entertaining interview, Phillipa shares her history with crewel work, why she spends so much time researching new designs, and how each piece of crewel work tells a story. Don’t miss Phillipa’s virtual lecture on March 14 or her upcoming online studio class Gawthorpe Peacock.

What were your first experiences with needlework and embroidery?

I suspect embroidery entered my life as a strategic escape plan.

My mother owned an ancient Singer sewing machine that required someone to turn the handle – an honour I tried very hard to avoid. According to family legend, my refusal may have been linked to an alleged attempt to shoplift curtain rings during a Saturday morning department store trip, after which I was deemed untrustworthy in public and left in the beautiful home of my ‘‘maiden aunts” instead.

As the second youngest of seven children, being left behind at seven years old turned out to be a gift. My doting great-aunts introduced me to embroidery, and they were patient, encouraging, and entirely free of sewing machines with handles. I still have the tablecloth I stitched back then—now very well used—and I still grow Primula denticulata in my garden, which will always remind me of those early lessons.

What drew you to crewel work embroidery in particular?

Embroidery is an art form where the colours are already mixed—and that was a revelation.

By this time two of my elder sisters were already art college students and their work always seemed to appear effortlessly, as if by magic. My own attempts at painting, however, involved enthusiastic overmixing and reliably resulted in a very committed muddy brown. Crewel work, by contrast, felt forgiving and joyful. The neighboring or intertwining threads do the work for you. The blending happens naturally, subtly, beautifully.

To my young brain—and to my much older one—it felt miraculous. And delightfully easy. As my six-year-old niece once told me, “It’s easy aunty Philly, it is just colouring in.”

You and your daughter run The Crewel Work Company. Why did you initially launch it?

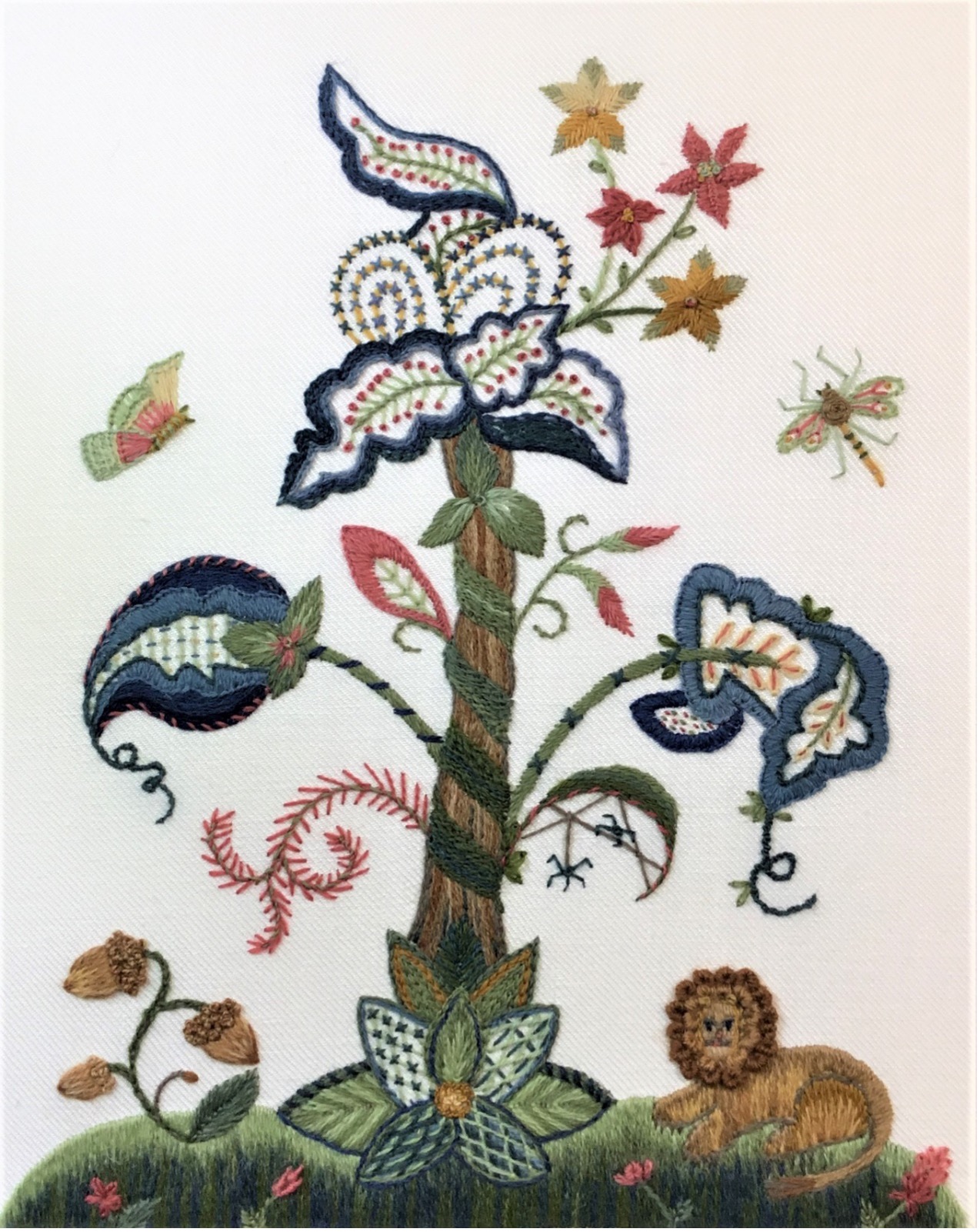

In 1993 I sold a design company where we made animal silhouettes on coir doormats for department and interior design stores. Somewhere during that transition, I became obsessed with recreating Jacobean linen twill—a fabric that was, at the time, almost impossible to source.

Eventually, I found a wonderful old Scottish weaver, Mr. Blackburn, who agreed to weave it for me. There was one condition: he would only produce 100 metres, because resurrecting his old loom wasn’t worth it for anything less. The Royal School of Needlework said they would take whatever I didn’t need—but in the end, they and I only needed five metres.

With 90 metres of linen twill and no obvious plan, I approached a buyer at John Lewis. As her very last order before leaving, and after offering sage advice, she gave me a chance to sell the kits nationwide. That moment changed everything. I’ve since been incredibly fortunate that people at many levels have believed in the sincerity of the designs—and here we are. My daughter has grown up helping and now running the company, and my son who also helped on many occasions, is now a design consultant. And my grandchildren think that it is slightly cool, depending on what we are up to!

Where do you draw inspiration for your crewel work designs?

From research, and a great deal of generosity.

I study examples in castles, country houses, museums, and auction houses. Owners, curators, conservators, and fellow embroiderers have been extraordinarily supportive, often sharing images and information about pieces that aren’t formally recorded.

Laura and I own several wonderful historic examples ourselves, and collectors such as Lanto Synge have been endlessly generous with their knowledge. Laura has a great eye, and many years experience working for a top auction house, so between us we have a lot of fun selecting designs which can translate to be enjoyed in the 21st Century. Crewel work has a quiet but passionate community, and I’m lucky to be part of it.

Your process for replicating historic designs is famously in-depth. Can you describe it?

It is not quick. At all.

I need to live with a piece of embroidery for a long time. I study it, return to it, think about it, dream about it. I sometimes wonder if I’ll ever reach the stage where I can walk into a castle, take a few photographs, do some quick sketches, and be ready to stitch a faithful replica. I’m not there yet.

Instead, I compare it with crewel work from nearby cultures, then contrast it with more distant ones. I look for origins, influences, and evolution. Only then do I freestyle draw it onto linen twill, matching wools, scale, colour, and form. That stitched drawing becomes my sketchpad.

I also study the wools themselves—what sheep breeds were available at the time, and where they came from. Often, I’m surprised to discover that the wool wasn’t local at all, but expensively imported. These details matter. They tell a story.

You say British crewel work reflects British culture. How so?

I think that I can wait until the lecture.

I will say this: Scottish crewel work is mostly quite different from English, and the British Isles have always had a strong regional bias. The stitches may be similar, but the voices are not.

Your virtual lecture, A Timeline of British Crewel Work, delves into how crewel work evolved from the early 17th Century up until the present day. The lecture description states that “the evolution of British crewel work has remained a reflection of the British culture.” Can you talk a little bit about the ways in which crewel work reflects British culture?

A clearer sense of where we fit.

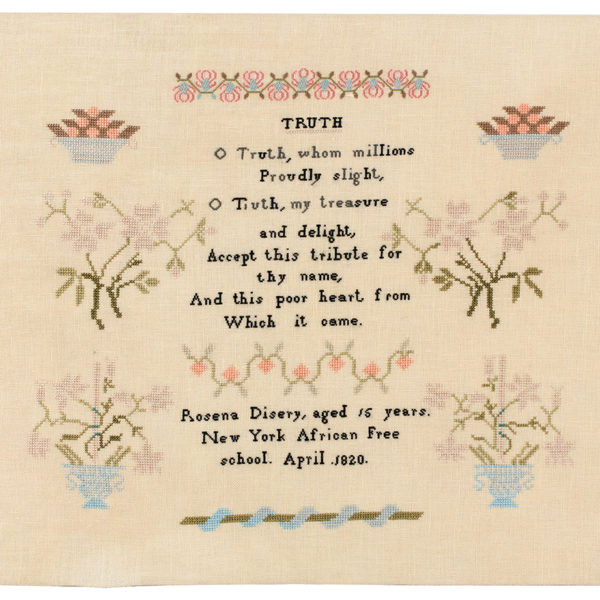

Crewel work has been made for extravagant display and for private pleasure, for status and for solace. How it was used and where it resides reflects how people lived, what they valued, and how open they were to influences from beyond their own borders.

I hope attendees leave feeling that embroidery isn’t just decorative history, but part of the long, tangled, very human timeline we’re all still stitching our way through.

Are there any exciting events you have coming up this year that you’d like to share?

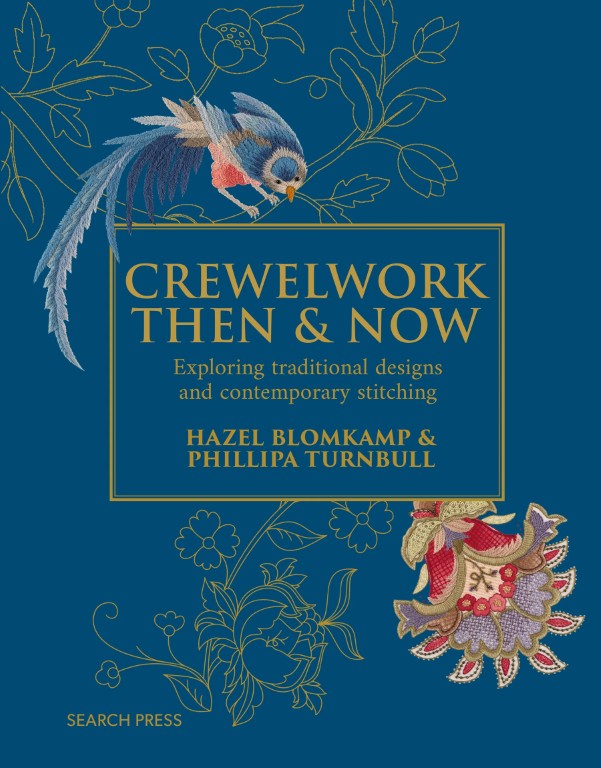

Very soon I will be in Australia to teach the designs in Hazel Blomkamp and my book, Crewelwork Then and Now, then for the last two weeks of February we are running our online festival with designs and films from Glamis Castle, Scotland.

This year we have two retreats coming up, one in our usual home-from-home Askham Hall in The Lake District, Cumbria where we live. The other is in Barcelona and Catalonia, where Laura lives.

I have been appointed Head Broderer for the Althestan Tapestry, which celebrates the creation of England in 927, very near to Askham and our home at Eaumont Bridge. This will involve over 100 crewel embroiderers and will be on permanent display.

After which we will be launching new designs, hosting our free Q&A sessions, and all the things needed to run our family business.

Where can interested embroiderers learn more about your work (social media channels, online groups, etc)?

www.crewelwork.com, admin@crewelwork.com. Facebook: crewelworkco, Instagram: crewelworkco, Youtube: @crewelworkco.