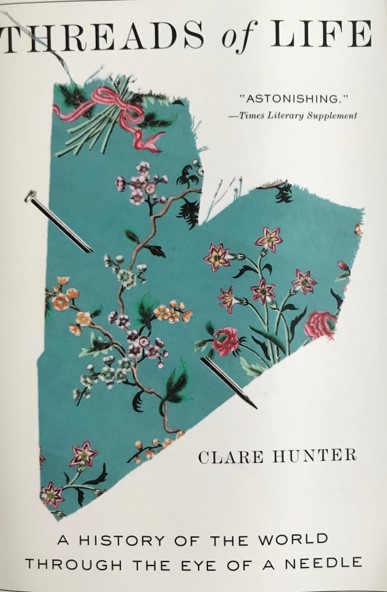

Does your needlework tell a story? In her books Threads of Life: A History of the World Through the Eye of a Needle, Embroidering her Truth: Mary Queen of Scots and the Language of Power, and Making Matters: In Search of Creative Wonders, author, needleworker, and artist Clare Hunter endeavors to uncover the hidden stories and lives of makers and crafters. In her upcoming EGA Virtual Lecture, Threads of Life, Clare will share the journey of research and discovery that led to writing Threads of Life, and how handcrafts are indelibly infused with history, meaning, and power.

What was your first experience with embroidery and needlework? How were you introduced to the art of needlework?

My mother taught me to embroider when I was about five years old. She took me to a craft shop in the city and let me choose from a carousel filled with a rainbow of threads and bought me little linen cloths, already stamped with floral designs. She also showed me some basic stitches: chain stitch, fern stitch, French knots, and satin stitch. I found it extraordinary that you could transform a simple piece of fabric into a riot of floral abundance with just a needle and thread. Embroidery brought me, and my mother, quietude. I loved to settle into its rhythm, and I found it soothing.

What kind of needlework do you enjoy doing?

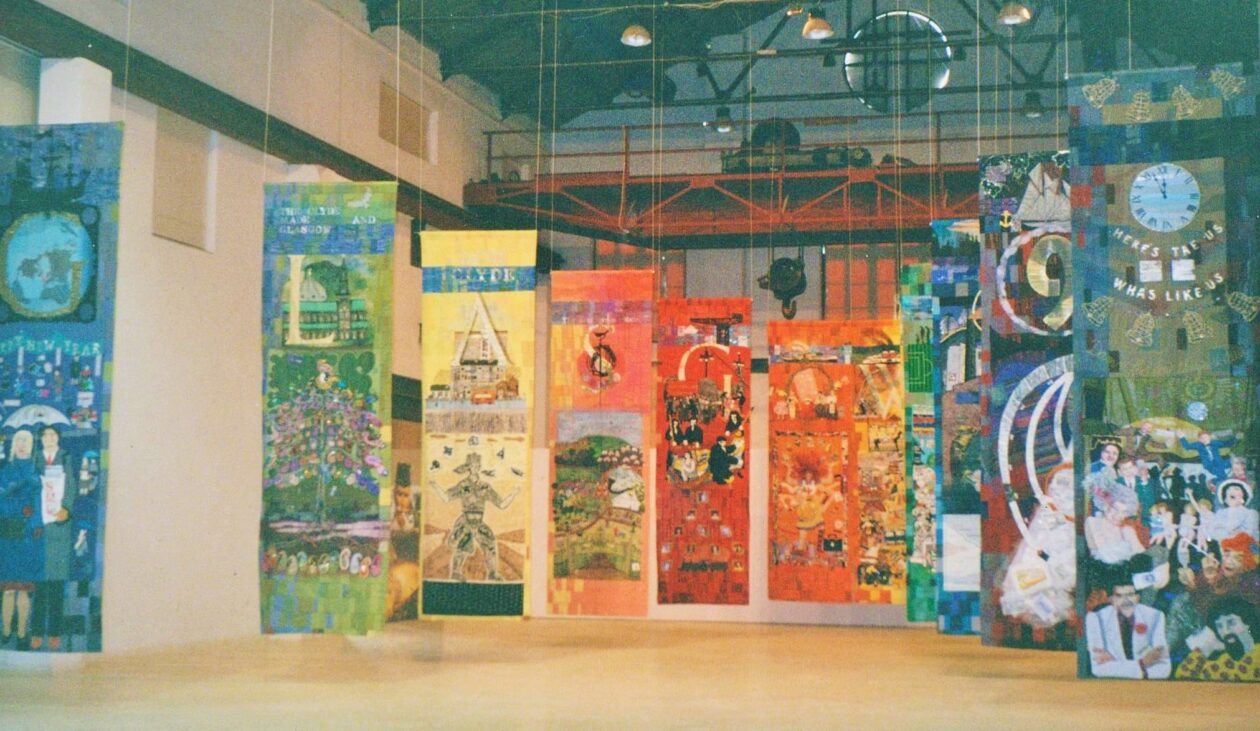

For most of my working life, I have been involved in helping communities make large, appliqued hangings that tell of their history, achievements, and concerns. I still love applique: the marrying of different textures and images with the embellishment of embroidery. But it’s not just about techniques. The kind of needlework I enjoy most is the sewing that I do with others. I love the gregariousness and camaraderie of people creating together, sharing skills and ideas, encouraging, and learning from one another.

What inspired you to write Threads of Life: A History of the World through the Eye of a Needle?

I was amazed that despite the hundreds of books written about needlework, so few ever mentioned why people sewed. That to me was what was interesting. Why did people take so much time and effort to make something from cloth and thread? I had curated a couple of exhibitions on the culture of needlework in different communities and the social, emotional, or political context behind what they made fascinated me. It felt to me that there were many stories of sewing that were in danger of being lost: stories that were moving, uplifting, and admirable, and I thought others might find them as interesting and significant as I did, and so I decided to write Threads of Life.

What do you hope readers take from Threads of Life: A History of the World through the Eye of a Needle?

I hope that it validates the value of what people sew and brings a greater understanding of what motivates people to sew. Sewing is not seen as an important craft. Rather, it is all too often viewed as something that is merely decorative. But that is far from the truth. Most people sew because they have something to say, something they want to celebrate, commemorate, protest about, or mourn. It is not just their heads and their hands that people use in their needlework, but their hearts.

Why do you believe it’s important to view history through the lens of needlework? What does this particular perspective afford us?

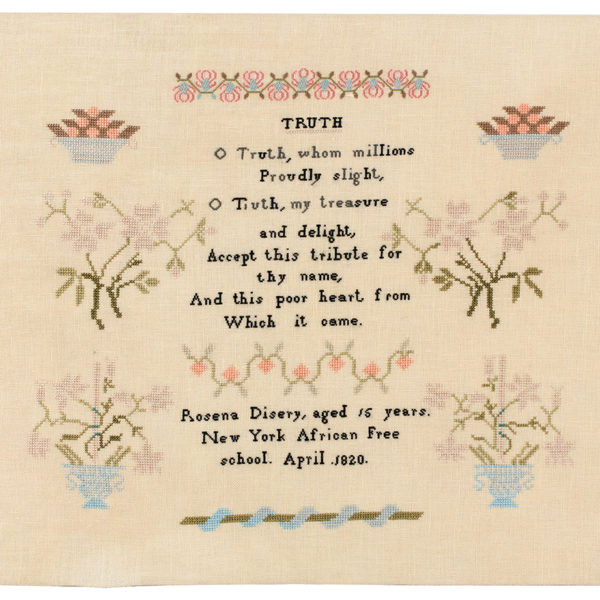

Much of the history of women has been written by men who deemed women the lesser sex. The voices of many women of the past remain unheard with their own illiteracy, or censorship and erasure of what they wrote leaving scant documentation on their lives, thoughts, and emotions. But, in their needlework, we have a form of material evidence. Viewing history through the lens of needlework allows us unedited access to women’s sewn testimonies and reveals what mattered most to them. My second book Embroidering her Truth: Mary Queen of Scots and the Language of Power explores the personal and political life of the doomed Scottish queen through the prism of the textiles she inherited, displayed, gifted, purchased, wore, and embroidered. It is, if you like, an alternative biography using contemporary source material—the 16th-century treasurers’ account books, court inventories, state papers, and Mary’s own letters—to piece together her story by correlating what was happening in her life with what she was choosing to do with her textiles. It allowed me to provide a more intimate portrait of her than mere historical fact could reach.

You’re both a writer and a textile artist, and one might say both practices create something larger and more expansive from the smallest components (stitches and words). How are these two creative practices similar for you? Why did they speak to you as creative pursuits?

I often say that I write the same way that I sew. When I make a large applique textile hanging, I choose the backcloth, stitch different motifs onto it in a variety of textures and colors, and then add details with embroidery. My approach to writing is very similar. I start off with a central idea, collect a plethora of stories and facts, trim them into themed chapters, and then work on the text adding insights and reflections for greater depth.

You organized a community enterprise in Glasgow called “NeedleWorks.” Can you tell us a little bit about the work of NeedleWorks?

I set up NeedleWorks as a community enterprise to provide employment for people who had creative talent but lacked the necessary qualifications to get into art school or find employment in textiles. We undertook commercial commissions and used the profit from those to subsidize community projects. For over a decade, we created large-scale stitched hangings with schools, museums, community centres, hospitals, and care homes involving local people and patients. Most of what we made was created in public, in shopping malls, museum galleries, or a hospital restroom so that others could see what was being made and join in if they wanted. We purposefully encouraged diversity: people of different cultures, ages, and backgrounds coming together to make something unique and learn about each other’s lives at the same time. The company won awards, media attention, and public affection. The most ambitious project was Keeping Glasgow in Stitches, a year-long participatory project in the city’s main art gallery and museum involving over 650 people in creating a series of twelve, 15 foot- long, textile calendars that captured the spirit, history, and personality of Glasgow itself.

Just for fun: What are you stitching right now? Also, do you have a favorite piece?

I have taken to rescuing textiles, unfinished embroideries, from a recycling charity, REMAKE, and taking them home to complete them. I like to think that whoever began them—prevented from completing them because of illness or death—would be pleased that their work was not in vain and that their efforts were appreciated and their intent honored. But I also like to applique and embroider berets in felt as gifts to family and friends. Felt is so soft to work with, and there are so many lovely colors.

Where should interested stitchers turn for more information about you, your writing, and your work?

My website, http://www.sewingmatters.co.uk, Instagram: @sewingmatters, and my email: clare@sewingmatters.co.uk

There are also a variety of online talks and interviews on YouTube.

My books (all published by Sceptre at Hodder & Stoughton) are Threads of Life: A History of the World Through the Eye of a Needle, Embroidering her Truth: Mary Queen of Scots and the Language of Power, Making Matters: In Search of Creative Wonders.