The next time you call EGA headquarters to learn more about EGA membership, or receive help researching EGA’s library, or feel inspired by a cool new design in the EGA shop, remember Lilly Higgs. Lilly Higgs is EGA’s Member Services Associate, and her job entails all of the above and more. Lilly has a background in fine arts, a love for EGA, and a fascination with employing, preserving, and celebrating historical methods of craft, from foraging plants to create natural dyes to devoting time to the meticulous art of handsewing garments. Lilly belongs to the next generation of needleworkers at EGA and presents an intriguing look at how millennial and Gen Z stitchers approach community and engagement with organizations like EGA. If you’d like to learn more about Lilly and EGA, reach out to her directly at lhiggs@egausa.org!

You are the Member Services Associate at EGA. What does that job entail?

Kind of anything and everything! I am often the first person that EGA members encounter with headquarters, whether it’s a phone call (people are always very surprised when I pick up and am, in fact, human), answering email inquiries, shipping out our pin and merchandise orders, and other correspondence. Most of my day-to-day work is assisting members with class registration, renewing or transferring their memberships from chapter to chapter, and other tasks with our database. However, I also am doing some neat design work in the background as well, like new merchandise (get excited!) and a bit with our print materials. I also manage the library books and study boxes, and am training for handling our collection, which is my favorite part of my role. I love seeing these pieces of history and handwork. I love to be inspired by the pieces in our collection.

How did you become interested in and involved with EGA?

Interestingly, I didn’t know about EGA before I started working here. While looking for work, I was looking for things I loved, searched “embroidery” and found a very mysterious job listing that said “must love embroidery.” When I was interviewed, it was entirely over the phone, and I wasn’t told who the employer was until the middle of the interview. I had my computer open for notes, looked up the organization, and felt all the air get sucked out of my lungs. I was so, so nervous and wanted this job so badly I didn’t even tell my mom who I’d interviewed for because I was afraid I’d jinx it. The first day, I ran around looking at all of the books, the collection and as much as I could lay my eyes on. I am still so astonished and so grateful I get to come and work with such a fantastic organization and wonderful people every day, and have the privilege of watching over its legacy.

What were your first experiences with needlework? Do you have a favorite needlework style or technique?

Most peoples’ experience with needlework begins with their grandmother teaching them. I remember specifically going to my Mamoo and asking her if she’d teach me, and she told me that she didn’t have the patience because I was a pretty energetic kid. I was a handful, with a big interest in art and absolutely zero interest in things like, say, dolls. However, I kept being drawn to fabric, fibers, and thread. My mom collects quilts, and we had giant, beautiful quilts hung on our walls as art all through my childhood, and we had a giant wooden spinning wheel (a great wheel) in front of the fireplace. I used to run my fingers over them and wonder about the hands that made them.

I became enamored with Japanese street fashion, cosplay, and manga around middle school, and I realized I couldn’t simply acquire those things at the Charlotte Russe in the mall, and so I taught myself to sew with what limited resources were available then. I was shy about dressing myself at first, and so, ironically, became incredibly interested in Asian Ball-Jointed dolls just before high school. This was a community of incredible artisans and makers for very accurate garments and accessories that had to be functional small-scale. Unlike dollhouses or Barbie-scale dolls, these garments used the same techniques as full-size clothing, so I was making tiny pockets my doll could tuck his thumbs into that were only about a half-inch wide, or dresses with little embroidered sleeves less than an inch wide. It was a total trial by fire, and honestly made the shift to sewing for myself feel easy. Seams weren’t 2 millimeters anymore! I delighted my dear and very confused grandmother with little stitched gifts of strange objects and small plush toys.

I ended up taking a fiber arts class in high school—one semester was fiber, the other semester was printmaking, I believe? Goes to show what stuck. I learned how to embroider there and was quickly stitching little clumsy daisies on my flareleg pants and Y2K denim backpacks. My teacher told me all of my stitches were messy, but I started doing soft sculpture and more.

Nowadays I’m doing more historical work, anywhere from Viking era laid-and-couched work and wool applique, to Norwegian bunad embroidery. I still very much like embroidery in mini and micro-scale, however, and I carried over some of my background in comics to do illustrative embroidery for larger pieces.

My favorite technique is crewel, and I actually ended up learning how to hand-spin thread to stitch with. I absolutely love the texture, the ‘bloom’ of the fluffy wool, and how much character it can add wherever it’s used.

From looking at your Instagram and website, you seem very interested in employing historical methods of stitching, dyeing, and sewing. Why are these historical methods so appealing, and what have they taught you about handcraft techniques?

I grew up going to Colonial Williamsburg and being intrigued by the historical costumes there, but I didn’t get into it until after doing cosplay for several years. As the technology ante was being upped in those spaces, I just realized I liked getting crunchier with how something was made. It made for a better story! What do you mean, I can go scoop up fallen acorns outside an Arby’s or drag chunks of kudzu out of a neighbor’s yard and dye with it?! That’s amazing!

There are so many methods we’ve simply forgotten or have been whisked away from us by industry, and it’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking people in historical eras are somehow less intelligent or less advanced than the modern era. Viking age peoples had the exact same brain mass as we do, had the same very nuanced and delicate societal struggles we do, and also employed extremely complex methods in order to have their garments made. Nothing was written down, and techniques were developed by word of mouth and repetition. I still stand in absolute wonder that folks in the 9th and 10th centuries could memorize card-weaving patterns that took 40+ cards, each with four strands, and complex directions—but then again, they weren’t trying to sort out their health insurance or navigate highway junctions.

Something I love is that historical work is allowed to be a bit clumsy at times. Turning Worth gowns inside-out and finding out they’re also held together with faith, straight pins, and basting stitches, or turning around 18th century bedcurtains and seeing someone’s crazy back knots is reassuring. Plant dyes can get splotches and interesting mottling. Spinning your own thread gets variety in shape and texture. It’s a very human thing, to reach back and touch another artist’s work, see how they thought “oops, I messed up. Well, thank goodness no one is going to look that close,” and I’m here in 2026 with a magnifying glass. I love that connection.

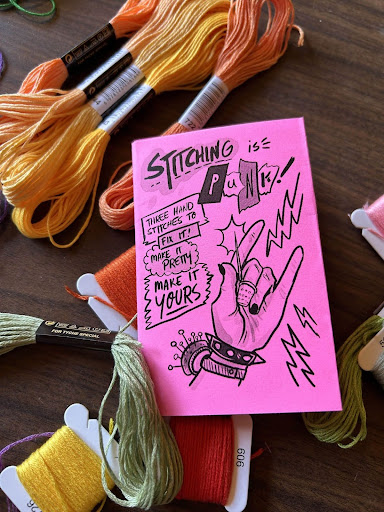

You have a background in comics, and recently wrote a zine called “Stitching is Punk” to educate teens on hand stitching. What’s the connection with comics?

Well, I’m certainly trying to make that connection! Almost all of my comic work is influenced by fiber work, either by using motifs and designs in the artwork itself, or in the narrative, such as having my protagonists practitioners of fiber arts. I created a comic called “The Spindle” set in the Viking Era about a girl struggling to learn to spin, based on my own frustration with learning a new art form. A long-form comic I’ve got on the burner involves a dressmaker’s shop set in a fantasy version of Norway, run by a trio of folkloric creatures each specializing in a particular craft– Spinning, Weaving, and Embroidery.

I also find comics to be an extraordinary gateway for learning new things. In my youth outreach with a local organization, I created a mini “zine” (short for magazine) to help my students learn a few simple stitches. Zines are incredible resources for self-publication and are enjoying a resurgence these days as people rediscover tactile media. My teens were so excited to learn, I realized there was a gap in books written from this angle.

So, my goal this year is to create a beginner’s introduction to embroidery stitches, techniques, and styles, using the format of a journal comic. It’s meant to be approachable and friendly, giving lots of resources for further study without bogging things down.

In the very messy landscape of digital overdrive, AI slop imagery and algorithm fatigue, a lot of younger generations are turning toward tactile media again, including fiber arts. I want to create something fun that appeals without overwhelming, and inspires instead of intimidates.

Your artist’s website says much of your work is inspired by Scandinavian folklore. What about this specific aesthetic and narrative do you find appealing?

Despite having no Scandinavian background, I am deeply fascinated by the overlap between nature, folklore, and craft. Many of the continent’s artistic influences, like rococo decorative painting, ended up passing through many interesting filters on the way to the far north. My specific focus is in Norway. Rosemaling, or rose-painting, is the folk art form of decorative painting floral motifs on objects, and many of these motifs carry on to embroidery patterns as well. The national dress, or bunad, usually carries these stylized, highly graphic flowers that feel beautifully traditional and yet stunningly modern.

Since coming to work for EGA, I have been to Norway twice for research. The first time I went to the Hardanger Folkmuseum, where I spent a good three hours glued to the display cases, drawing notes. I wrote an article for Needle Arts about this trip, which was published in March 2024. In May 2025 I returned, and this time had the extraordinary opportunity to visit the collection of the Norwegian Institute of Bunad and Folk Costume to research the development of embroidery styles for bunad. Everyone there was extremely kind and considerate. I hope to share some of my findings soon! I’m currently learning Norwegian in order to help read the history books dedicated to folk costume and embroidery, most of which are not translated at all.

Norwegian folklore is the meeting of man and nature, and often, craft is deeply woven into the narrative, whether from a hero’s occupation, or the act of craft is what ultimately outsmarts the trickster trolls; my favorite is the Huldra; a woman seen as beautiful from the front, and yet, terrifying from the back as she is hollowed out like a tree trunk, and she often has a tail like a cow. She comes to dance with human villagers, and is often described wearing blue folk dress. If you spot her tail and are polite, saying something akin to “Oh, miss, the hem of your slip is showing!” then she might demurely tuck it away, and your crops and flocks will flourish. If you react badly, however… Well, something terrible indeed might happen!

I love the strangeness of it, it’s not present in a lot of modern continental European folktales. It’s beautiful, and just a bit dangerous. A bit like embroidery, really!

You’ve mentioned that “the world of costume sewing, both historical and fandom-based, is a thimble. We all know each other or know friends.” I would imagine that leads to a lot of cross-pollination of methods, with artists inspiring one another, as well as a preservation of techniques, motifs, and styles borrowed from the historical and used in fandom pieces. Can you talk a little bit about how you see these worlds informing one another in the world of needlework?

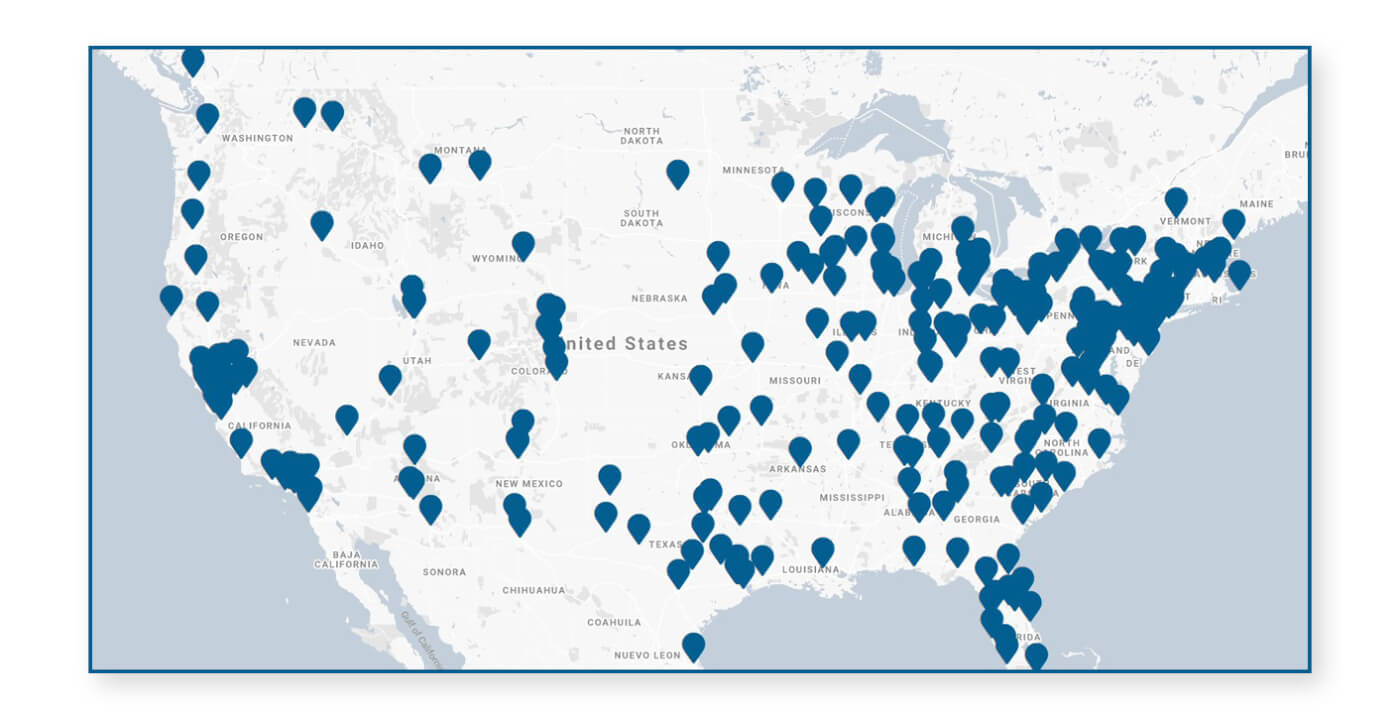

I confess I’m not the first person to use the metaphor of a thimble. That comes from my friend Abby! This is actually a good example of this: I found out about a Hobbit-themed, official LARP (Live-action Role Play) event happening very close to my town, endorsed by the Tolkien estate, called the Brandywine Festival. I signed up instantly, within the hour of tickets being on sale, and then climbed into the organizer’s email inbox to inquire if I could do a workshop on handspinning, and some demos of embroidery. (Next year the “Embroiderer’s Guild of the Shire” will have actual meetings!) I heard back from him– turns out he worked at the same Viking reenactment space I went through and we had mutual friends. Through being present in this community, I became friends with Maggie Roberts, who was friends with the costume team writing the guide, which includes Abby Cox, Nicole Rudolph, Morgan Donner, Vivien Lee, Rachel Maksy, Christina and Roo DeAngelo, Queen Astraea and other costumers from all over the country.

We quickly realized that we ALL knew other friends through various costuming events and endeavors—from historical reenactment to fandom-based costuming—and that made becoming friends faster. As it stands, it turns out that our incredible photographer, Alexandra Lee, who is working with us photographing EGA’s collection has been some of my friends’ photographer at conventions, and also Maral Agnerian’s, who just worked with us on a Virtual Lecture, who knew Amanda Haas, who I used to cut fabric for… It’s that sort of thing. When we talk to one another, we play a “okay, do you know ___?” and usually two will get us a common thread. We all fit in a thimble.

Most of my friends come from a generation awkwardly sandwiched between where sewing and embroidery were taught in schools, and when it became widely available online. Most of us had to learn the hard way, pre-modern internet, and yet after in-person classes were becoming harder to come by for more advanced techniques. There was also in some spaces a stigma on our projects—some who didn’t like that we were “wasting” these techniques on costumes, or folks who were very preoccupied with flawless, master-level execution on the first try, and so our greatest resource became our community. Someone who wouldn’t question WHY we needed to make a Sailor Moon brooch out of goldwork and velvet, but could absolutely get us the tutorials we needed to do it. They were also willing to incorporate mixed media and unusual tools into designs, which might not be covered in a traditional how-to.

We ended up learning from books, but we mostly learned from each other. When one of us cracked a method like smocking, goldwork, or beading, most of us turned around and instantly started teaching one another. It formed an incredibly close ecosystem of learning and teaching, and it became incredibly valuable to have a tight community. When one of us made a mistake, we all learned from our frustration, and when one of us solved it, we all celebrated together. The urge to share this knowledge is inherent in all of my friends and I love seeing it in the EGA communities I work with as well.

As for “cross-polination” it’s less like pollination and more like when one of us does something we think is cool, we grab our friends by the ankles and drag them into doing what we’re doing. Or we post about doing something feral in a corner and then suddenly all of them see it and say “how do we do THAT?” Working together always makes something more fun and less frustrating. It’s a very exciting process of gushing and hooting and hollering on messaging apps, with heinous amounts of stash materials.

Where do you draw inspiration for your own embroidery designs? What does your design process look like?

We’ve already talked about my Scandinavian folk influence, but my other favorite time period in art is Arts and Crafts and the following Art Nouveau movement, particularly the Scottish arm that took place in the Glasgow School of Art at the time. There was extraordinary work being produced then in every medium, but there are some absolutely incredible pieces made by embroiderers who were also illustrators, like Margaret and Frances MacDonald, Ann Macbeth and Jessie Newberry. The intersection of illustration and storytelling with needlework in this time period is incredibly powerful to me.

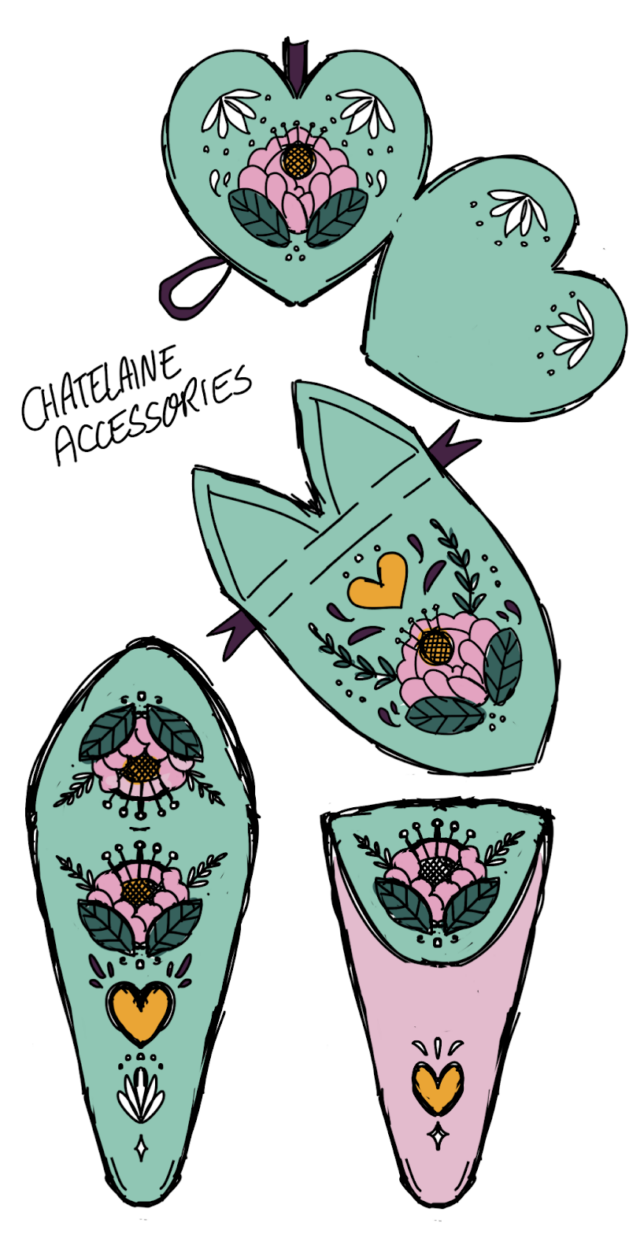

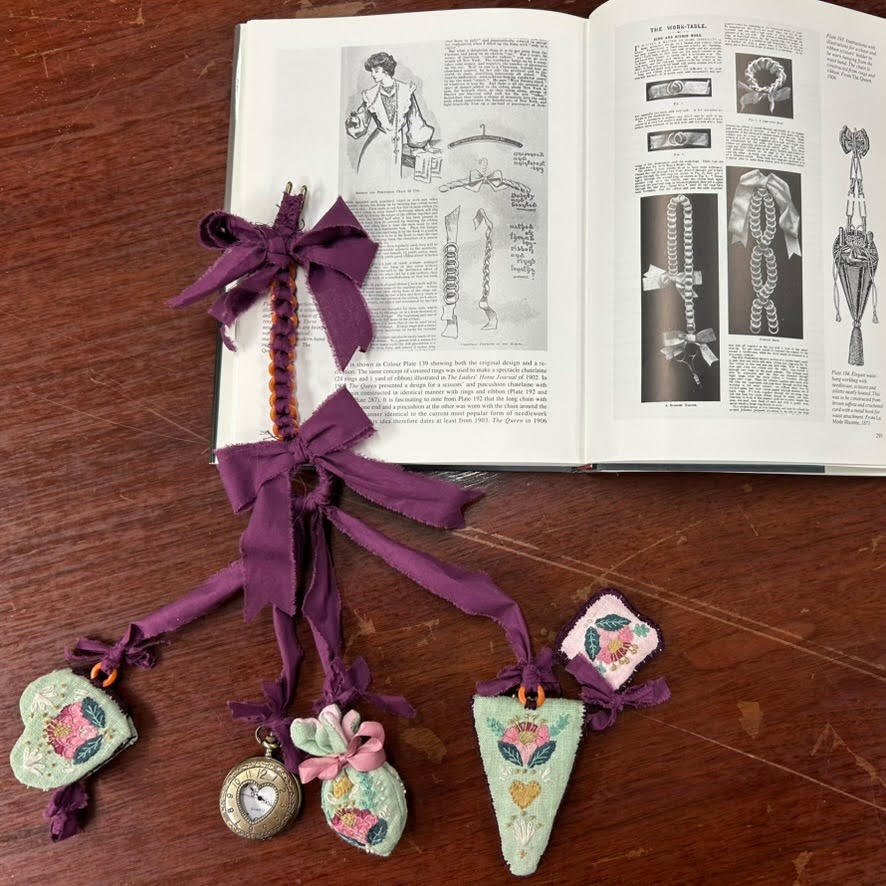

My training is as a comic book illustrator, and so I always think of drawings first. I design the pieces almost as a complete character design and then work backwards. It’s a lot of gathering of references of how this kind of piece was made with one material or another, what techniques were used, what might work better, and what appeals to me. I either use Pinterest or Milanote to gather my references and thoughts.

Here is a design I’m working on right now– the deadline is in March, and gosh, I hope I finish it! It’s pretty tight.

Then I usually do a tiny test-piece to be sure I like it:

For example, for my chatelaine, I drew the design, which is based on Os-style Norwegian folk art, and then did a single flower to test.

I tried it with satin stitches and absolutely hated it. Then I tried using a buttonhole stitch to create the “fanning” small-scale, and was much happier!

I also realized I didn’t quite care for the metallic thread at this scale, and so switched up the design a bit. I like doing little tests; working small means that you can work up a test design rather quickly.

My chatelaine I’m a bit nervous to share, as I’m a bit afraid that the extremely skilled among us will point out every flaw, but it’s important to note this is a chatelaine to be carried by a hobbit in the shire, not the halls of a fine house, so, it being a bit whimsically hand-hewn is part of the charm.

See more of Lilly’s artwork at lillyhiggs.com/art and follow along her stitching adventures on Instagram at @saccharinesylph.